I discussed Permanent Record on NPR's Here and Now program yesterday. If the "Listen" link at the top of that page doesn't work (it was a little wonky for me yesterday), you can go straight to the audio of the segment here.

For those of you who've been asking what's next for Permanent Record, several possibilities are in the works. More details soon.

Friday, November 4, 2011

Thursday, November 3, 2011

This just in: I'll be discussing Permanent Record in a fairly lengthy segment on today's edition of the NPR program Here and Now.

You can use this page to see when (or if) the program is available on your NPR affiliate.

I'll post the archived audio once it's available.

You can use this page to see when (or if) the program is available on your NPR affiliate.

I'll post the archived audio once it's available.

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

The bad news is that most of the Slate series is still not functioning properly (grrrrr); the good news is that I've been given permission to republish the entire series here on this blog.

The first Slate article is, for the most part, fine (some of the photo links are a bit wonky, but it's mostly OK), so you can read that on Slate. You're better off reading the second, third, fourth, and fifth articles here. The photo interface here on the blog isn't as elegant as the one on Slate, but at least all the links work, all of the text is present and accounted for, and so on.

So if you want to take in the entire series, or pick up where you left off, here you go:

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

More developments soon.

The first Slate article is, for the most part, fine (some of the photo links are a bit wonky, but it's mostly OK), so you can read that on Slate. You're better off reading the second, third, fourth, and fifth articles here. The photo interface here on the blog isn't as elegant as the one on Slate, but at least all the links work, all of the text is present and accounted for, and so on.

So if you want to take in the entire series, or pick up where you left off, here you go:

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

More developments soon.

Saturday, October 8, 2011

Isn't that nice? It's a little charm (actual size: half an inch wide), given to me by the lovely Kirsten Hively -- her way of congratulating me on Permanent Record's success.

Meanwhile: The folks at Slate are in the process of restoring the five-article series to its full functionality. It's not quite there yet, but it's getting close. I hope to post updated links to the series in a few days. Thanks for your patience.

Thursday, September 29, 2011

If you've been trying to access the Slate series and haven't been able to do so, the explanation can apparently be found above. Slate unexpectedly (at least to me) unveiled a new page format today, one consequence of which is that the Permanent Record series has become a complete mish-mash. The old URLs for the articles no longer work, and I don't want to give out the new URLs yet because the content is all jumbled up -- photo links are in the wrong places, entire swaths of text have disappeared, etc. A serious mess -- extremely frustrating!

I know some of you were taking your time to get through the series, or had bookmarked it with plans to read it later. Well, now you can't. Yes, that really stinks. Even worse, the editor and art director who produced the series both left Slate just as the articles were being published, so now the whole project is orphaned. Grrrrrr. I've sent a note to Slate's ed-in-chief, asking for the content to be corrected, restored, or whatever. Keep your fingers crossed.

Wednesday, September 28, 2011

It was exactly 15 years ago today -- Sept. 28, 1996 -- that I attended my friend Gina Duclayan's 30th birthday party, which was held in the gymnasium of the old Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan (shown above). It was during that party that I came across a discarded file cabinet filled with old report cards. I didn't realize it at the time, but Permanent Record was born that day.

So happy birthday to Gina, and happy birthday to Permanent Record -- forever linked in my mind.

I talked about Permanent Record on the radio yesterday, on WNYC's "Brian Lehrer Show." The audio of the segment is embedded below.

I'm about to take a short vacation, which means I probably won't be posting here over the next week or so. But I'll definitely be updating this site in the weeks and months to come, so sign up for the RSS feed or e-mail notifications (both of which are available at the top-right of this page) if you want to stay abreast of new developments. Thanks.

Monday, September 26, 2011

The woman on the right is Donna Protter. She and her mother, Lucille Fasanella, were profiled in the third article in the Slate series (Lucille is the one who saved her beautiful sample book and was flagged as a "troublemaker" by the school's staff). On the left is my friend and researcher extraordinaire Diane George, who found Donna and her family about six months ago.

Donna and Diane were among the 20 or so people who joined me for a Permanent Record party this past Saturday. I was so busy talking, thanking people, and generally feeling happy that I didn't take nearly as many photographs as I should have, but here are a few shots.

These are my longtime friends Daniel Radosh and Gina Duclayan:

It was at Gina's birthday party back in 1996 that I found the report cards, so it's not a stretch to say that the entire project started with her. She and Daniel took a large batch of cards that night, saved them for over a decade, later donated them to me for the purposes of this project. I'm super-grateful to them for all their help and support.

The two guys in this horribly composed photo are Kenny Lauterbach (on the left) and Matt Weingarden:

They're the other two friends were took some report cards that night back in 1996. They too saved their cards for more than a decade and then donated them to me. Matt has been one of my closest friends for many years, but I hadn't seen or spoken to Kenny in ages until I decided to pursue the Permanent Record project.

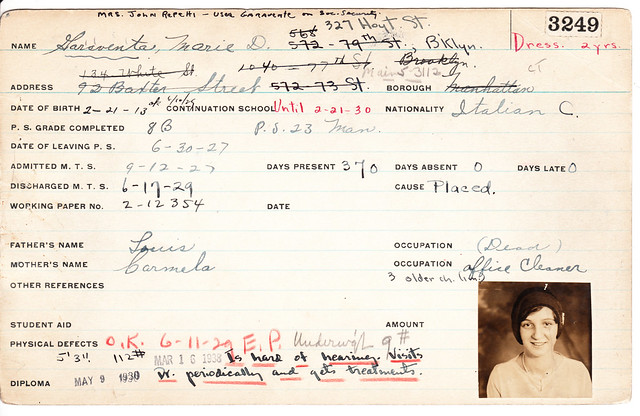

This is Dr. Robert LaPorta, the son-in-law of Marie Garaventa, whose report card was featured in the first and second installment of the Slate series:

Robert's wife is Doretta LaPorta, Marie's daughter, who I interviewed extensively for the series. Unfortunately, Doretta wasn't able to join us on Saturday because of a family emergency, but I was extremely happy that Robert came in her stead. They were both incredibly gracious about having a stranger visiting their home and asking all sorts of personal questions.

Many people who read the Slate series mentioned how much they liked the photo interface. That tool was designed by this guy, Slate designer Jeremy Singer-Vine:

Jeremy actually left Slate before the series was published (he took a new gig at the Wall Street Journal) but continued to work on the project during our final week of production, on his own time. I can't thank him enough for all his contributions to the finished product.

There were lots of other people in attendance, but I didn't get decent photos of them. Still, it was a great time, and a nice way to conclude this phase of Permanent Record.

I say "this phase" because I hope to continue researching and writing. Maybe there will be a book, or maybe there will be more Slate articles. And there will definitely be more material here on the blog. Stay tuned.

I'll be discussing Permanent Record Tuesday morning on "The Brian Lehrer Show" (WNYC radio). My segment is due to start at 11:40am Eastern. You can access the live audio here, and I'll link to the archived audio once it's up on the WNYC web site.

Friday, September 23, 2011

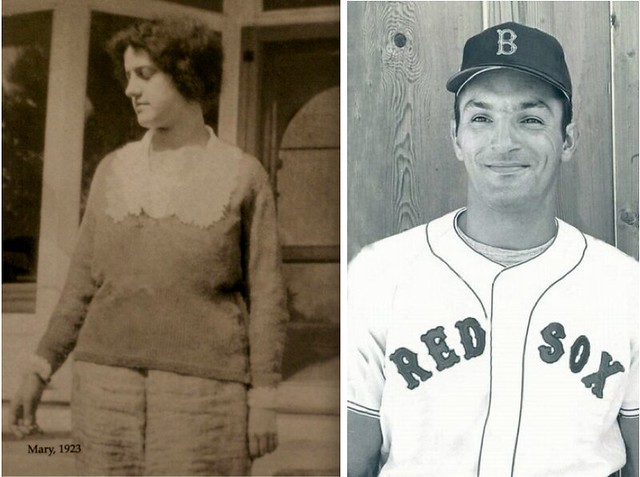

On the left is an 18-year-old girl named Mary Lorang; on the right, a baseball player named Carmen Fanzone.

These two people, who never knew each other, helped bring some closure to Permanent Record -- at least for me. Their stories are told in the series' final article, which is up now on Slate.

My thanks to everyone who's offered feedback on the project. Many of you have asked what will happen now that the Slate articles have been published. For now, I plan to keep updating this blog periodically, and it's possible that the project may continue in another medium -- stay tuned.

I discussed Permanent Record yesterday on Minnesota Public radio. You can listen to the segment here.

Thursday, September 22, 2011

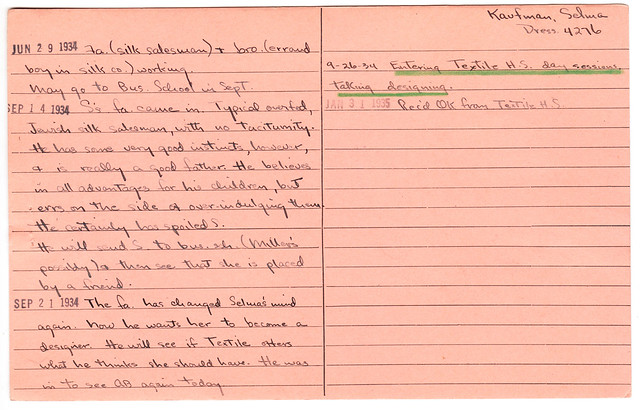

The card you see above comes from the file of a student named Selma Kaufman, who attended Manhatttan Trade in the 1930s (you can click on it for a larger version). The entry for Sept. 14, 1934, begins with: "Selma's father came in. Typical overfed Jewish silk salesman, with no taciturnity. He has some very good instincts, however, and is really a good father."

Yeah, those Jews, always with the good instincts. I must say, I'd never heard of the stereotype of an overfed silk salesman before, nor had I ever encountered the word "taciturnity."

The Manhattan Trade report cards are filled with offhand commentary like this -- sometimes offensive, sometimes heartbreaking, always fascinating. Today's Permanent Record entry on Slate focuses on this commentary. Check it out here.

I'll be discussing Permanent Record today (Thursday) on Minnesota Public Radio's Midmorning Show. I'm told I'll be on from about 10:40-11am Central Time. You can access the live streaming audio here.

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

One reason the Permanent Record project has been so interesting is that I was lucky enough to have found report cards from a school that was extremely well documented. The book whose cover you see above was written in 1910 by one of the school's founders, and it explains a lot about the school's founding and early workings. The whole book is available online, as is one of the school's early annual reports. Even better, a 16-minute silent film about the school was shot in 1911 (if you have a few minutes, it's definitely worth watching). All of these resources helped me understand and interpret the information on the report cards.

The history of the school is the subject of today's Permanent Record article on Slate. Along the way, we'll take a look at a few students and their descendants, and we'll also see what the school building is like today. The article is available here.

Special Event: This Saturday, Sept. 24, I'll be hosting a small Permanent Record gathering in Brooklyn, New York. Attendees will include some of the family members I've interviewed, some researchers who've assisted me during the project, some people from Slate, and so on. We have room for a few more people, and it occurred to me that it might be interesting to have some readers on hand. If you'd like to attend, get in touch and I'll give you the details.

Tuesday, September 20, 2011

Last Friday I showed you a photo of Doretta LaPorta posing with her mother's report card. Today I have a short video clip of Doretta talking about her mother and the report card.

Doretta and her mother -- and how I tracked them down -- are the focus of today's Permanent Record article over on Slate. You can check it out here (click on the "2" at the top of the page).

Monday, September 19, 2011

What you see above is how the Manhattan Trade School report cards look today (well, about 25% of them -- I have three additional boxes). When I first acquired them back in 1996, each individual student's file was stapled together, and they stayed that way until I began the Permanent Record project about two years ago, at which point I removed the staples so the cards would be easier to work with. Some of the cards have little rust stains where the staples had been.

I thought about saving the staples. A serious historian or conservator would have done that, right? Historic staples! But that seemed like a bit much, even for me, so I just threw the staples away.

Anyway: The Permanent Record series on Slate finally kicks off today, and the first installment is all about the cards and how I acquired them. The series begins here.

Friday, September 16, 2011

The first entry on this blog showcased the report card of a student named Marie Garaventa. What you see above is Marie's daughter, Doretta LaPorta, holding that report card -- a tangible link to her mother's life.

As I've explained before, the principal research challenge of Permanent Record has been the fact that Manhattan Trade was a girls' school, so most of the students got married and changed their names, making it very difficult to track them. Over the past two years, I've made contact with fewer than 20 families. Some of them opted not to speak with me; others were happy to talk but live far away, so I had to interview them by phone; and then there were those, like Doretta, who I was able to meet in person.

At some point in the process I got in the habit of having these people pose with their loved ones' report cards. I wish I'd done it from the beginning -- there were a few who I missed and haven't had a chance to revisit. The ones who I did photograph are shown here:

All of these people will be profiled in the Permanent Record series on Slate.com, which will kick off on Monday. I'll keep posting a few items here on the blog, but for the most part I'll let the series speak for itself next week. Thanks for reading.

Special Event: Next Saturday, Sept. 24, I'll be hosting a small Permanent Record gathering. Attendees will include some of the family members I've interviewed, some researchers who've assisted me during the project, some people from Slate, and so on. We have room for a few more people, and it occurred to me that it might be interesting to have some readers on hand. If you'd like to attend, get in touch and I'll give you the details.

Thursday, September 15, 2011

December 3rd, 1915, was apparently a busy day for Miss Beagle, who ran the job placement office at the Manhattan Trade School for Girls -- or at least it was busy for her assistant, who had to type up at least two letters, as you can see above. I suspect there were several other similar letters sent out that day.

As you can see, both of these letters are addressed to students who had failed to claim their diplomas. Here's the backstory: After students at Manhattan Trade completed their coursework and training, they were required to demonstrate a proficiency in their chosen trade (dressmaking, millinery, or whatever) in the workplace. Only then could they apply for a diploma. Apparently some students didn't bother with this step and simply kept working. The letters shown above appear to be part of a broad attempt to contact past students who were diploma-eligible.

"Proficiency" in a student's trade was usually deemed to have been established after a year. One of the letters shown above was sent to a dressmaking student named Margaret Griffin, who had been finished her coursework way back in 1910 -- more than five years before Miss Beagle wrote to her. She responded with the following letter:

It's a little hard to read, so here's a transcription:

Mr Dear Miss Beagle,

Received your letter. Thought I would get an opportunity to go down and see you personally, but have been so busy. So I dropped these few lines letting you know that I would be delighted to receive a diploma.

I have worked in Lord & taylor for two season and went to McCreary last October, a year ago. Thanking you for your past kindness I remain

Margaret Griffin

According to Margaret's file, she received her diploma on January 14, 1916.

The other letter was sent to a decorative boxmaker named Jennie Guaraglia. Her file contains no indication of any response to the letter, and it appears that she never applied for or received her diploma.

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

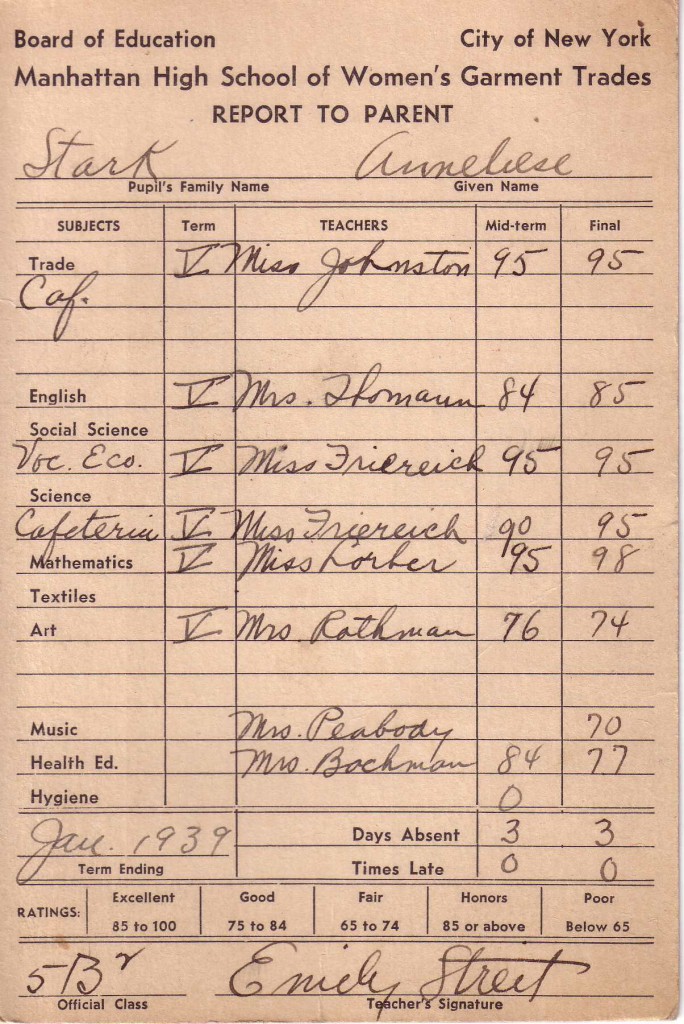

Yesterday I told you a bit about Anneliese Stark, whose report card I found on the web while doing some research. The photo you see above shows her in 1940, when she was 19.

Anneliese -- whose name is now Anneliese Smith -- now lives in an assisted-living facility in Baltimore. She is the oldest living graduate of the Manhattan Trade School for Girls that I have encountered (although the school had changed its name to the Manhattan High School of Women's Garment Trades by the time she attended). Her grandson, Frank Diller, who had posted her report card on his blog, graciously arranged for me to interview her over the phone a few weeks ago. We talked for a little over 15 minutes. Here's how it went:

Permanent Record: Frank, your grandson, explained to me that when you attended the trade school, you were living in a home for girls [essentially an orphanage], is that right?

Anneliese Smith: Yes, that's right, after my mother died.

PR: Was that home in Manhattan?

AS: It was in the Bronx. 318 Mosholu Parkway.

PR: You remember the address!

AS: Yes, it was a millionaire's home, and they took care of 28 girls. They were 12 to 18 [years old]. I think it was about five or ten millionaires who sponsored that home.

PR: Were you already attending the trade school when you began living there?

AS: No. I had missed two years of school because I'd been taking care of my mother, who was sick. [Anneliese's mother died of throat cancer when Anneliese was 13.] Nobody even bothered to see whether you were in school at that time. And then when I went into the home, that's when I started school again. They sent me right to the trade school.

PR: Did any of the other girls at the home go to the trade school?

AS: No, I was the only one.

PR: Do you know why they decided to have you go to a trade school, instead of a conventional high school?

AS: I guess because I had missed so much time.

PR: And when you entered the school, what trade did you choose to focus on?

AS: Well, I was interested in cooking, baking, stuff like that. So it was cafeteria management, I think it was called. But I took all the other courses also -- math, science, all that stuff. It's all there on my report card. I hadn't seen that in years until my grandson found it when I was moving.

PR: They were still teaching sewing and dressmaking at that point, right?

AS: Oh, yes. And they had beauty shop also. Teaching how to cut hair and all that.

PR: But you were more interested in cooking.

AS: I didn't really know what I wanted, honestly.

PR: Well, very few people do at that age. What do you remember about the school? Do you think it was a good school, and a positive experience for you?

AS: I think it was, yes. I enjoyed being there. The teachers were very nice. One time they took us up to Rye -- Rye, New York -- where there were rides and things like that.

PR: Oh, Rye Playland?

AS: Yes, that's right. That's where we were. We had a great time. We had a picnic first, and then we enjoyed the rides.

PR: It was still exclusively a girls' school at that point, right?

AS: Yes it was, mm-hmm.

PR: And the teachers and instructors -- were they all women?

AS: Yes, I think they were, yes.

PR: So there were really no men anywhere in this building.

AS: No, not really.

PR: After you finished your education, did the school help you find a job?

AS: No, I went to Pratt Institute for a year.

PR: Oh! And what did you study there?

AS: Same thing -- cafeteria management. But I never followed through with it.

PR: You never went into that field?

AS: No. I went into the service [the Army] when I was 21. After that, I did work at Stouffer's restaurant in New York for a while.

PR: Was that before you went into the service?

AS: Yes. It was on Fifth Avenue -- I think near 42nd Street. I don't know if it's there anymore.

PR: I don't think it is.

AS: But Stouffer's dinners!

PR: Yes, those are still around. What did you do at the restaurant?

AS: Whatever was needed. I was in training. I worked there for, oh, I guess it must have been almost a year. And after I came out of the service, I worked at Chase National Bank.

PR: Later on, when you were married and cooking for your family, do you think the skills and some of the things you learned in school…

AS: Oh yes, it was helpful.

PR: So even though you didn't go into a restaurant career, your experience at the trade school helped you in later life.

AS: Yes, it did.

PR: Did you maintain any kind of contact with the school over the years?

AS: No, I didn't.

PR: I've seen your report card, but do you know if you saved any other artifacts or paperwork from your time at the school?

AS: I have my yearbook, but that's about all.

PR: Really?

AS: My grandson has it someplace, yes.

PR: Wow. I'll have to ask him about that. Would it be okay if he showed it to me?

AS: Yes, that would be fine.

PR: Anything else you remember about the school, maybe about the building itself?

AS: It, it -- it didn't look like a school. It looked more like a warehouse, I think. It didn't feel very scholastic. But they had a cafeteria on the first floor, where people would come in to eat, and we served ’em.

PR: Well, I don't know if it looks like a warehouse, but the building is still there, and it's still a school, although it isn't a trade school anymore. Now, when they were teaching you cafeteria management, what sorts of things were they teaching you?

AS: We did all the cooking, and then we served the lunch.

PR: So you were feeding the other students?

AS: No, we were feeding people who'd come in from outside.

PR: Oh -- so people in the neighborhood could go to a coffee shop, or a diner, or whatever, or they could come get lunch from you?

AS: Yes. We always had soup and salads, hot food. Rolls, cakes, and pies.

PR: And would you be supervised by the school's staff?

AS: Yes. Miss Johnston.

PR: Would you or the other students come up with recipes, or were they given to you?

AS: They were given to us.

PR: And at that time, were you thinking, "This is good food, we're serving a good meal"?

AS: Well, at the time I was upset because I'd lost my mother, and I went on a hunger strike. So that was rough on a teacher. She had to coddle me and make me eat.

PR: Now, you were commuting all the way from the Bronx to East 22nd Street. Was that a long commute?

AS: Yes, it took about 45 minutes to an hour. I used to ride the train, the subway.

PR: On the back of your report card, there are signatures from…

AS: From Miss Cole.

PR: And who was she?

AS: She was the superintendent of the home. She was wonderful -- oh, she was so good to me.

PR: And she signed your report card because she was your legal guardian.

AS [starting to sound a little tired]: Yes.

PR: I want to thank you so much for sharing your time and your stories with me.

AS: Oh, you're welcome. I hope I've helped you a little bit, I don't know.

PR: Oh, you have. Thanks again.

And there we are. I actually learned a fair amount from Anneliese. For example, I hadn't known that the school was offering cafeteria management or cosmetology instruction in the late 1930s. I also didn't realize the school had a retail lunch operation. Some years earlier, when Manhattan Trade's vocational training centered on garment work, a small dress shop, selling the students' creations, had operated on the school's first floor. Perhaps the lunch business replaced the dress shop as the school's vocational focus shifted, or perhaps the two retail outlets coexisted. Another mystery for another day.

After speaking with Anneliese, I asked Frank about the yearbook. He found it and was then kind enough to loan it to me. You can see Anneliese's senior photo at the bottom-right corner of this spread. Unfortunately, the yearbook doesn't have much additional information about what the school was like during this period -- it's mostly just head shots, a few poems and essays, and a long list of boosters.

One last thing: Frank told me that when Anneliese turned 16, Miss Cole -- her guardian at the orphanage -- recommended that she visit her father, whom she hadn't seen since her parents had divorced years earlier. As Frank described it to me, "She went to his apartment and knocked on the door. Her father opened the door and promptly shut it in her face. Anneliese heard a woman in the apartment ask who was at the door. 'No one,' her father replied."

Frank has assured me that it's fine to share this story, but I couldn't bring myself to ask Anneliese about it. It just seems too heartbreaking. So here's a teen-ager who had to overcome the death of her mother and the rejection of her father, yet managed to build a life and a family for herself. It's an inspiring story -- she must have been very strong. My sense of it is that she still is.

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

Although I typically use the term "report cards" when referring to my collection of Manhattan Trade School student files, that's really a bit of a misnomer. These cards weren't sent home for parental review, and they contain all sorts of information that wouldn't normally be found in a standard report card. My cards are really the students' permanent records -- the files that are kept at the school and never shown to the students or parents.

I always assumed that Manhattan Trade used conventional report cards as well, but I'd never seen one until I stumbled across the one shown above, for a student named Anneliese Stark. (The school name at the top of her card, Manhattan High School for Women's Garment Trades, was the third of the four names the school would have during its 90-year history, but it was still essentially Manhattan Trade.) It was posted last winter on a blog maintained by Anneliese's grandson, Frank Diller. I came across his blog post while doing some routine Google research on the school.

I got in touch with Frank and explained my project to him. He was kind enough to tell me about Anneliese's life story. Here's the short version: Anneliese was born in Stuttgart in 1921, the youngest of three children. Her father came to America in the mid-1920s and then sent for his family. By the time Anneliese was 13, her parents had divorced, her father had distanced himself from his children, and her mother had died of cancer, so Anneliese was placed in a girls' orphanage in the Bronx, where it was decided that she should attend Manhattan Trade. She later attended Pratat Institute in Brooklyn, joined the Army during World War II, and then married and raised a family in the Baltimore area.

But here's the best part: Anneliese is still alive. She's in an assisted-living facility and turned 90 last month. Frank said he thought she could handle a short interview and agreed to ask her if she'd be willing to speak with me on the phone. She said that would be fine, so I recently called her. We talked for about 20 minutes.

This raised a question for me: Should Anneliese's story be included in the series of Permanent Record articles that will be appearing on Slate.com next week? After all, I'd been wanting all along to match up a Manhattan Trade report card with a living student, and here was a chance to do just that.

But the more I thought about it, the more Anneliese seemed like her own separate category. For one thing, her report card was never in my possession. In fact, it had been in her possession all along, so it's not as though I was reuniting this card with its long-lost subject, which is what I had hoped to do with this project (and am still hoping to do, although the odds now seem rather remote). Also, Anneliese's conventional report card contains much less information than the permanent records in my collection, so there wasn't any compelling commentary to ask follow up on, no unresolved storylines to ask about.

I don't mean to suggest that Anneliese's story isn't fascinating -- on the contrary, it is. But I ultimately decided that it belonged here, on this blog, instead of in the Slate series. I'll present a transcript of my interview with her tomorrow.

Monday, September 12, 2011

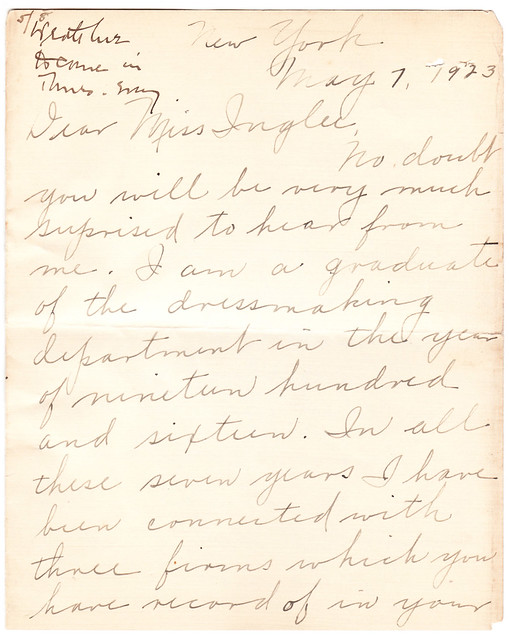

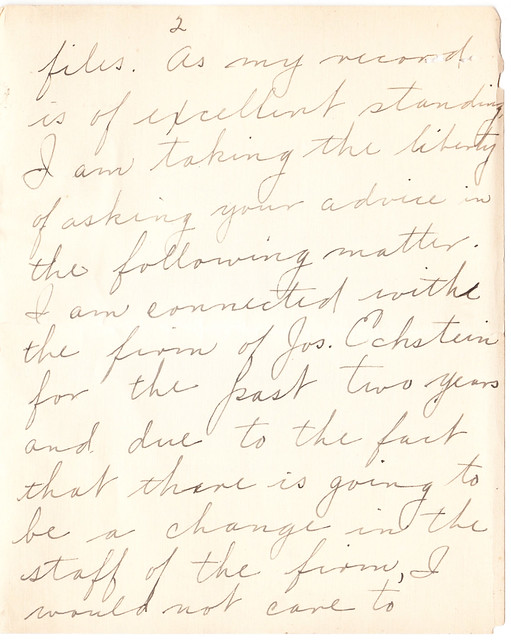

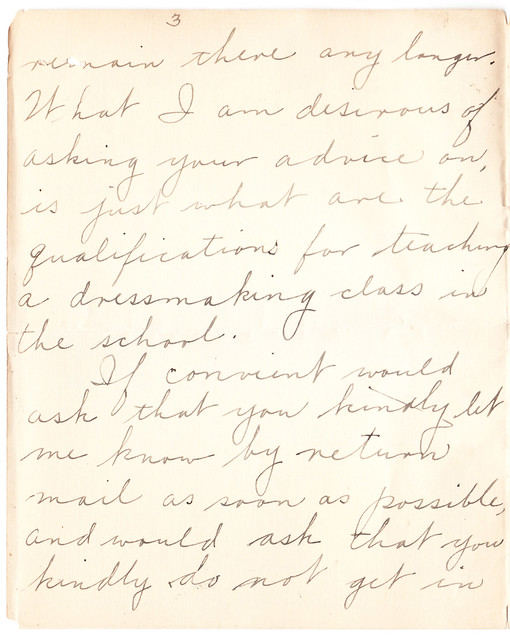

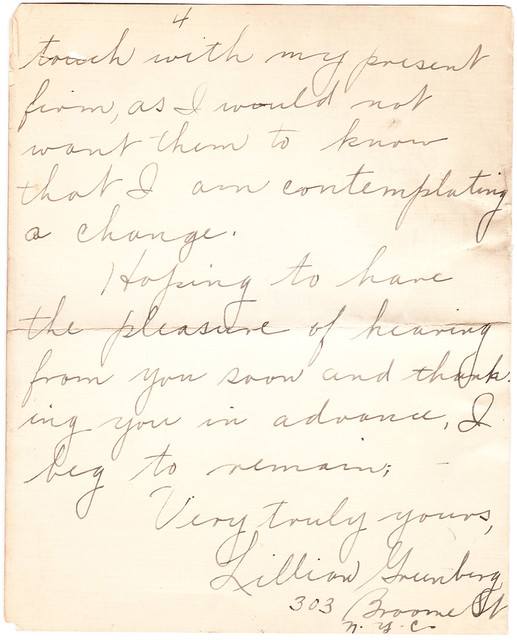

The letter shown above appears in the file of a dressmaking student named Lillian Greenberg, who attended the Manhattan Trade School for Girls in 1915 and ’16. It's a little hard to read, so here's a transcription:

May 7, 1923

Dear Miss Inglee,

No doubt you will be very much surprised to hear from me. I am a graduate of the dressmaking department in the year of nineteen hundred and sixteen. In all these seven years I have been connected with three firms which you have record of in your files. As my record is of excellent standing, I am taking the liberty of asking your advice in the following matter.

I am connected with the firm of Jos. Echstein for the past two years and due to the fact that there is going to be a change in the staff of the firm, I would not care to remain there any longer.

What I am desirous of asking your advice on, is just what are the qualifications for teaching a dressmaking class in the school.

If convenient, would ask that you kindly let me know by return mail as soon as possible, and would ask that you kindly do not get in touch with my present firm, as I would not want them to know that I am contemplating a change.

Hopeing to have the pleasure of hearing from you soon and thanking you in advance, I beg to remain

Very truly yours,

Lillian Greenberg

303 Broome St.

N.Y.C.

Interesting! I believe this is the only example of a student in my report card collection asking for a teaching position at the school. It's not clear if Lillian was hired. Personally, I doubt it (among other factors, she was about to turn 22 years old -- far younger than the school's other instructors), but a note at the top of her letter reads, "Wants her to come in Thurs.," so apparently her request was taken seriously.

My collection does include a case of a student who circled back to the school for a different reason, with a different request. It's one of my favorite storylines in the entire report card collection, but I'm saving it for the Slate series -- which, incidentally, starts one week from today.

Friday, September 9, 2011

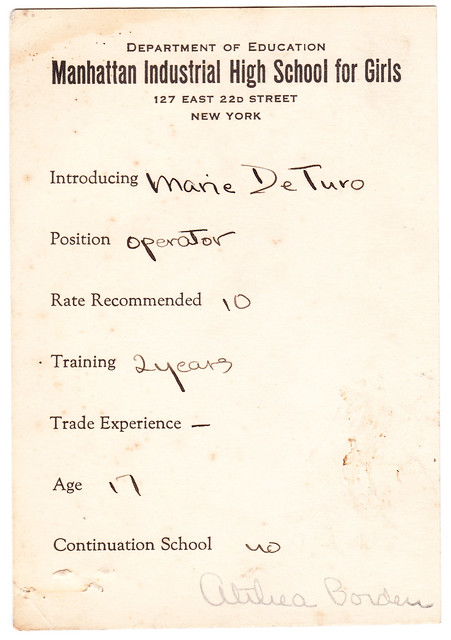

Here's another rare document: a small card that a student was apparently supposed to take with her when sent to her first work assignment by the Manhattan Trade School job placement office. (Manhattan Trade had changed its name to Manhattan Industrial High School around 1930, about four years before this card was filled out.)

The card is blank on the back, and there's indication that it was intended to be mailed. I think the girl -- in this case a sewing machine operator named Marie DeTuro -- was simply supposed to bring it to her first job and present it to the employer, who had presumably been told by the school to expect her arrival.

This is the only card of its type that I have. Nothing like it appears in any of the other students' files, and it's not clear to me why it was retained in Marie's. Did she forget to bring it? Did she return it for some reason?

I love the use of "Introducing" at the top of the card, as if Marie, about to begin low-wage garment job, were a debutante. Which, in a way, I guess she was.

Thursday, September 8, 2011

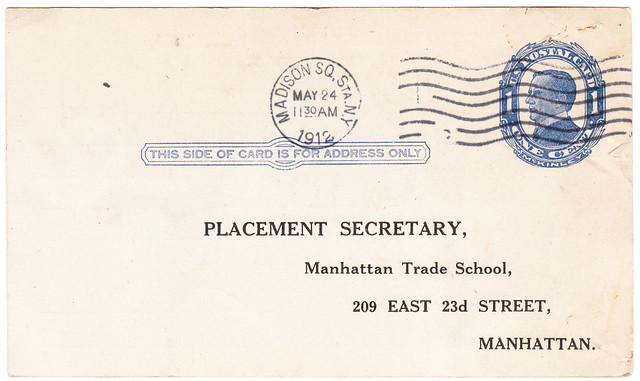

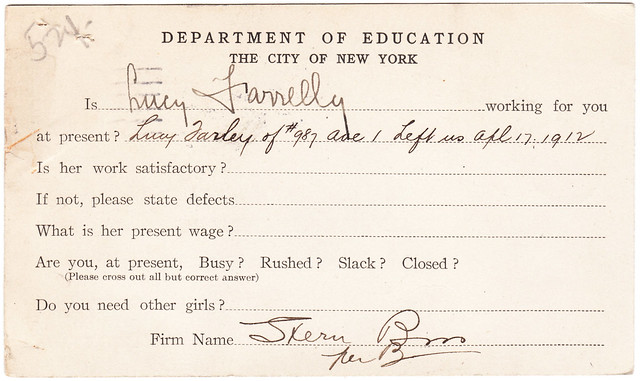

I've talked a fair amount about how the Manhattan Trade School for Girls would arrange employment for its students, and how the girls and their employers were then encouraged to report back on each other to the school. But how was that reporting done?

The answer comes from the postcard shown above (the two images are just the two sides of the same card), which gives us a peek into the way the school communicated with employers. Out of the 395 student files in my collection, only two of them have a postcard like this one, so the cards were apparently discarded after the information from the employer was transcribed into the girl's record.

The original reports from the girls regarding their work experiences weren't usually kept on file either. I have such original documents from only one student: a dressmaker named Ella Seeber, whose file contains three postcard reports on her work assignments. Again, this information was routinely transcribed into the girls' employment records, and then the cards were apparently tossed away. It's not clear why three of Ella's cards were retained.

Note that the card at the top of the page is nearly 100 years old!

Wednesday, September 7, 2011

One of the most engaging aspects of the Manhattan Trade School report cards is the way you can reconstruct certain storylines from the data in the files.

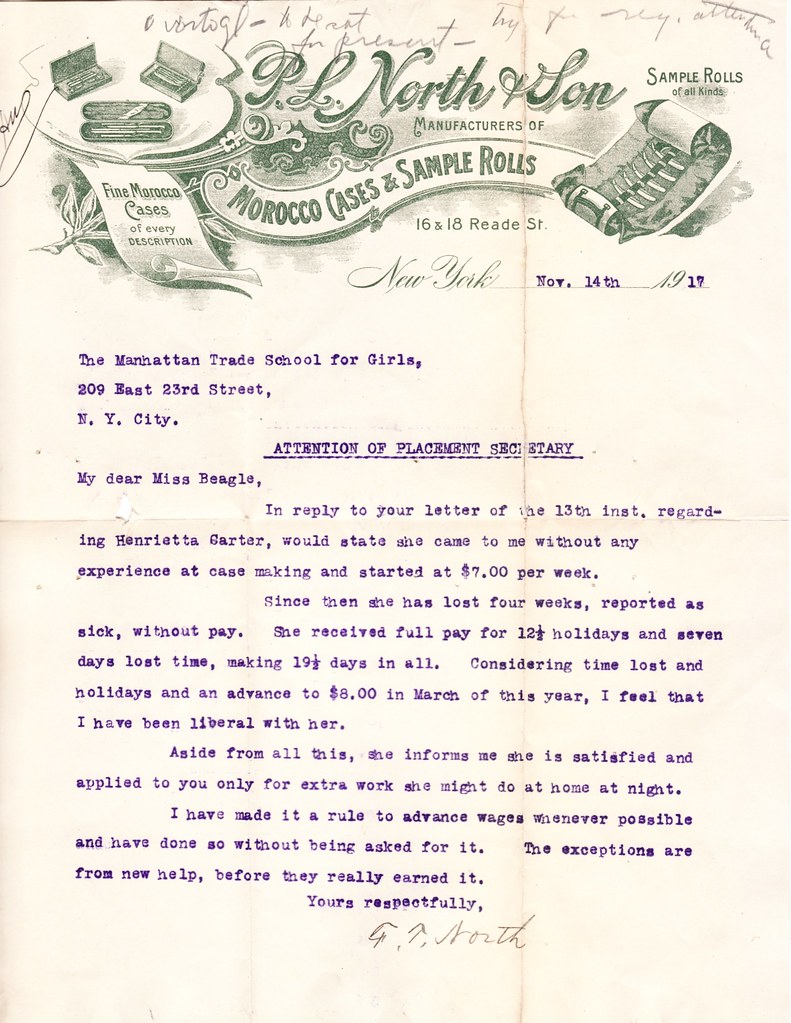

Take, for example, the case of the letter you see above, which is in the file of a dressmaking student named Henrietta Carter, who attended Manhattan Trade from 1910 to 1911 (note that her father was a "coaler" -- a nice term). How did that letter come to be written? Here's how we can reconstruct the pieces of the puzzle:

1. Henrietta, like most Manhattan Trade Students, was placed in a series of jobs. If you look in the far-right column of that card, you'll see each of her work assignments was given a number.

2. Those numbers correspond to the numbers in the far-left column of these cards, which have comments from Henrietta (marked with a check in the "Girl" column) and from her employers (marked with an x in the "Employer" column) regarding her work experiences. For example, on May 26, 1911, for employer No. 3, Henrietta reported that she was "Leaving because Miss P. is disagreeable and cross about work." If we go back to the list of employers, we see that employer No. 3 was a Miss Pilcher.

Are you following all of this?

3. Employer No. 21 was L.P. North -- the company whose letterhead is shown at the top of this entry. (As you can see on the letterhead, the company name was actually P.L. North, not L.P. -- a rare slip-up in the Manhattan Trade recordkeeping.) If we look at the comments regarding that job assignment, we see that Henrietta had said, "Want more money -- raised 5 mo. ago." And then it indicates that "H.B" had written to the employer.

4. H.B. was Miss Beagle -- Manhattan Trade's job placement secretary, to whom the letter was addressed. So Miss Beagle, responding to Henrietta's plea for more money, had apparently written to P.L. North, inquiring as to whether Henrietta could receive a raise. And F.T. North (perhaps the "Son" in the company's name?) essentially responded by saying that Henrietta was a bit of a slacker, that he'd already been lenient with her, and that all she really wanted in the first place was some "extra work she might do at home," not a raise.

And there you have it.

Want to go even deeper? Consider this: Henrietta was a dressmaking student (this is indicated at the top-right corner of her main card), so how did she end up working for a company making "Morocco cases and sample rolls"?

The answer lies in some of her work comments. At one point she had reported, "Dr. says I am too nervous for D. ["D" refers to dressmaking.] Would like to combine dressmaking with shipping." Then, 10 days later, "Dr. says must take something entirely different from dressmaking, such as nurse maid." And then, nearly two months later, at the bottom of the card, "Must not do any sewing!"

Fast-forward about four and a half years: Henrietta said, "Would like to try novelty -- too nervous for sewing." The term "novelty" refers to the making of fancy decorative novelty gift boxes. Three weeks later, the school had placed her at P.L. North -- not a novelty box operation, but not a standard garment-sewing job either.

And that's how Henrietta ended up making Morocco cases. And how she eventually complained about not getting a raise. And how her employer said she didn't really deserve one.

Now imagine untangling 395 of these puzzles, and you'll get an idea of what my report card collection is like.

Monday, September 5, 2011

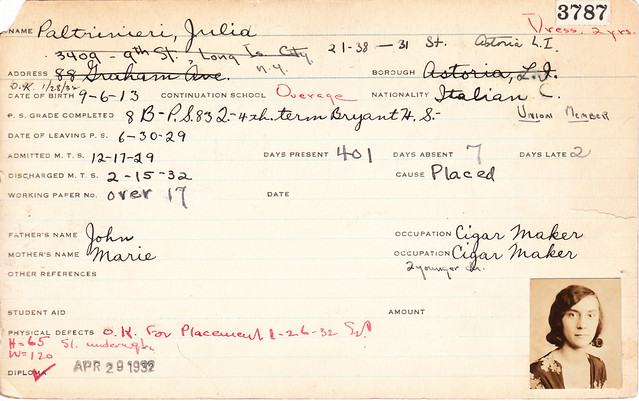

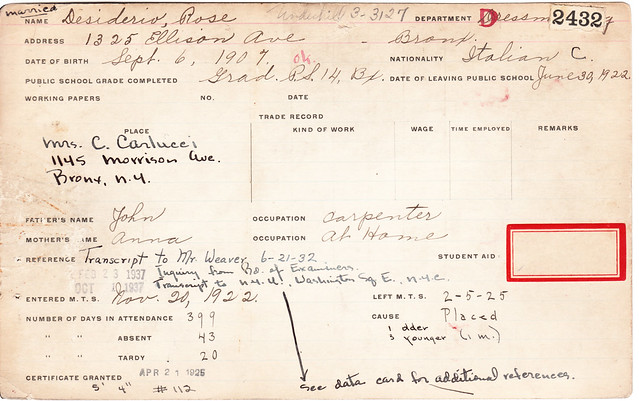

What do these two Manhattan Trade School report cards have in common? If you look at the two students' dates of birth (located in the upper-left portion of the cards, just under the street address), you'll see that they were both born on Sept. 6 -- which is today.

If Julia Paltrinieri is still living, she's turning 98 today. And Rose Desiderio (who later married and became Rose Carlucci), if she's still alive, will have 104 candles on her cake.

The reality, of course, is that both of these women are probably deceased. But you never know -- I've been unable to track down their families, so I can't be certain either way. Just to be safe: Happy birthday, Julia! And happy birthday, Rose!

Update: Reader Lloyd Davis did a bit of on-the-spot research and determined that Julia Paltrinieri died on August 15, 1999, a few weeks shy of her 86th birthday. R.I.P.

Sunday, September 4, 2011

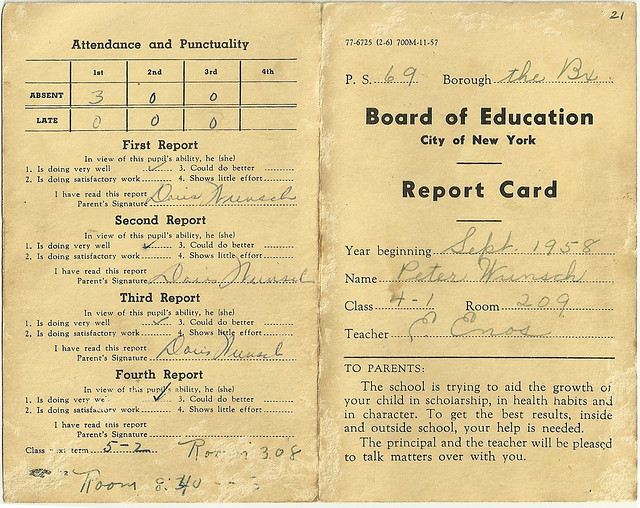

The report card shown above (it's the same card -- the two images show the outer and inner panels) isn't from the Manhattan Trade School for Girls. It's from P.S. 69 in the Bronx, which is where Peter Wunsch attended school while growing up in the 1950s. He had saved his report cards and was kind enough to scan this one and send the scans to me.

This document is more in line with what most of us think of when we hear the term "report card." It was sent home for the student's parents to review and sign. The Manhattan Trade student files, although I frequently refer to them as report cards, are actually the students' permanent records, and are filled with much more information than a standard report card. Still, conventional report cards like Peter's have something that the permanent records do not: a parent's signature. It may not seem like much, but sometimes something as simple as signature can be something to cling to, a cherished reminder of a loved one who's passed away.

"The reason I sent you this particular report card is it's one of the few in which I received a good grade in conduct," says Peter. He also sent along his second grade class portrait (that's him in the back row):

Click to enlarge

Peter had some interesting commentary on this photo:

The teacher, Ms. Friedlander, wearing pearls, hosted a really early Sunday-morning AM radio show that we all listened to regularly.

The chubby boy on my left, Alan Friedlander (no relation), worked in the World Trade Center and was one of the 9/11 victims. There was a campaign earlier in the year to re-name P.S. 69, and Alan’s name was one of the nominees. I believe the entire naming is stuck in NYC bureaucracy. …

I notice in looking back that the then-middle class neighborhood was almost entire white. I always thought of myself as the outsider because I was the only Jewish person in the class. I never thought about how Cathy (Korean adoptee) or Mercedes (the tall Hispanic girl) must have felt.

I recently went back and toured the area. My father’s candy store is now a dental clinic and both the synagogue I attended and the movie theater are both Hispanic churches.

Unfortunately, I haven't saved any of my old report cards. Have you saved any of yours? If so, and if you're willing to share them, please send them my way and I'll feature them in a future installment of Permanent Record.

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Most of the Manhattan Trade School report card files consist of four or five individual five-by-eight-inch cards. But some of the files have additional paperwork: notes from the school staff, letters from social workers, and, as you can see above, notes from doctors. These extra documents -- sometimes still tucked into their original envelopes -- are among my favorite aspects of the Permanent Record project, because they introduce a new set of voices to the chorus of schoolmarminess that's found throughout most of the report cards.

I also love that these notes and letters are often printed on lovely old stationery. In the case of the letter shown above (which was in the file of a student named Florence Gattusa), I was intrigued by the address on the letterhead. Second Aveneue between 7th and 8th Streets -- I know that block. It's in the East Village, and I've walked on it countless times over the years. In fact, I used to walk on it a lot on my way to See Hear, the now-defunct fanzine shop on East 7th Street.

Hmmm, I thought, could there still be an optometrist's office at 124 Second Avenue today? A quick check of Google Maps reveals that the address is now a convenience store. But is it the same building where Florence had her eyes examined by Dr. Rubin in 1931? Probably not -- the oldest certificate of occupancy on file for that address with the city's Department of Buildings (or at least on the department's web site) is dated 1973. This isn't definitive -- sometimes there are older records that aren't available on the web -- but the likelihood is that the old building was torn down and replaced by the current one.

That's part of the fun, and sometimes the sadness, of Permanent Record -- getting to see how New York has transformed and reinvented itself over and over in the years since the students attended Manhattan Trade.

A few other quick notes about Florence:

• Her teachers absolutely loved her. Check out all of the glowing comments on her report card.

• The school placed her in a sewing job with a downtown operation called Progressive Underwear. That's one of the many excellent business names scattered throughout the report cards.

• Here's something I hadn't even noticed until I began working on this blog entry: At one point Florence and the other workers at Progressive Underwear apparently went out on strike. I can't recall seeing any other references to organized labor actions in the report cards; then again, I didn't even notice this one until just now, so I may have to take a closer look.

Sunday, August 28, 2011

What you see above is not a report card, obviously -- it's an old police mug shot.

Or, rather, it's a Photoshopped image based on an old police mug shot. It's one of several 1950s mug shots that have been subtly doctored and are currently being reproduced and sold by a Cincinnati operation called Larken Design.

I learned about Larken -- which consists of two women in their late 20s -- in this article, which ran in Sunday's New York Times. It says that the photos had been discarded more than a decade ago by a California sheriff's office (the "Cincinnati Police Department" lettering on the sign is one of Larken's Photoshop adjustments to the original photo) and had somehow ended up at a flea market and then at a Nevada antiques shop, where one of the Larken partners, Tara Finke, found them two years ago.

Sounds kind of familiar, right?

Finke and the other Larken partner, Megan Scherer, began selling prints, posters, and notebooks based on the mug shots earlier this year, and they've been a hit at craft shows and on Etsy. In the Times article, Finke is quoted describing the products' appeal like so: "I definitely think it’s the mystery. I kind of feel like I’m getting a glimpse of something I’m not supposed to.”

What Finke was referring to there, whether she realized it or not, was voyeurism -- the cheap thrill of getting a peek into someone else's private affairs, the tingle we get from the public airing of something private, and the potential for shame if we're caught looking. Voyeurism is a very specific term, because it indicts the viewer in some sense of culpability or responsibility, and it's at the heart of what most of us find appealing about found objects. One big weakness in that Times article is that it doesn't address voyeurism at all and instead describes the Larken products as exercises in ’50s nostalgia, which I think is way off the mark. (Another weakness is that the article doesn't mention Mark Michaelson's seminal book of found mug shot portraits, Least Wanted. If you like Permanent Record, you'll really like that book. Trust me.)

I've spent a lot of time thinking about privacy and voyeurism ever since I found the Manhattan Trade School report cards 15 years ago, and especially since I decided to use the cards as the basis for a media project. For starters, I wondered if there were any legal issues, so I consulted an attorney. (I'll spare you the details, but the short version is that I've been assured that I'm on safe legal footing for this blog, for the Slate series, etc.)

But the bigger issue, I've always felt, is less legal than ethical, or maybe cultural. Once I saved the report cards (when I found them, they were about to be thrown out), what responsibility, if any, did I take on? What moral imperatives, if any, accrued to me? As I've mentioned in previous entries on this blog, many of the cards include very personal information about the students -- is it wrong for me to have access to that information? Is it wrong for me to share it with others (i.e., with you)? Is it wrong that the cards with the most heartbreaking tales of woe and pathos tend to be the ones that are, for lack of a better term, my favorites? Does the fact that the students are now dead make it all okay? Or does it make it worse, since they're no longer around to grant or deny me permission to share their stories?

Then there's all the history documented in the report cards -- history about New York City, about the education system, about the garment business, and so on. Would it have been wrong not to share that history? Would it have been better if I blacked out the students' names and/or photos when showing the cards?

My feeling about all this is, basically, that it's complicated. I've tried to be sensitive to issues of the students' privacy, and I've also tried to be more than just a voyeur. I don't ever want the primary response to the report cards -- from me or from anyone else -- to be limited to, "Wow, look at that old stuff, that is so fucking cool!" I fully agree that there's tremendous temptation to respond in precisely that way, though. Frankly, it's more or less how I reacted on the night I found the cards.

But as I quickly realized, the important thing to remember about the report cards -- and about mug shots like the ones Larken Design is peddling -- is that they're not just evocative artifacts or romantic curios from the past (or, um, vehicles for a media project). They're real documents of real people's lives, and that's something I've always tried to keep in mind. That's a big part of why I decided to track down some of the students' families, because I wanted to make the students feel less like ciphers and more like real human beings. My hope is that I'm telling these stories in a way that makes the students seem real to you as well.

Meanwhile, I've sent a note to the Larken Design gals, telling them about Permanent Record and suggesting some obvious parallels between their project and mine. They're probably swamped with e-mails today, since they were featured in the Times, but I'm hoping they'll get back to me so we can compare notes.

Thursday, August 25, 2011

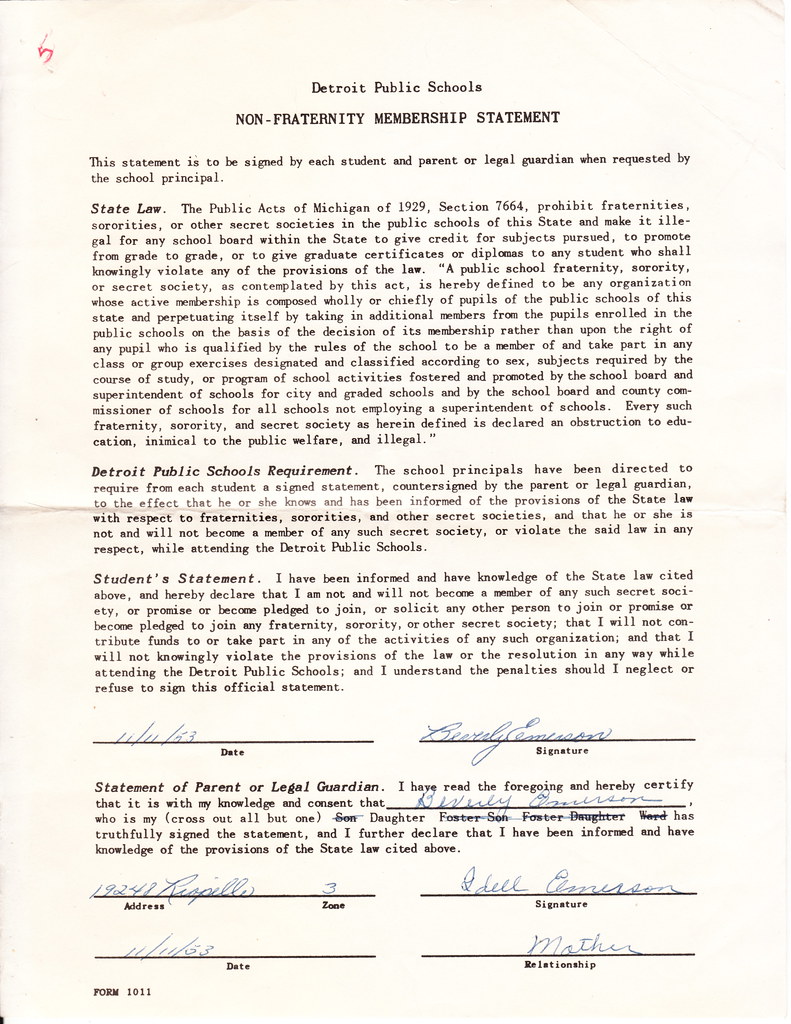

A few posts ago I featured the odd-seeming Non-Fraternity Membership Statement that was included in the student records I found at the old Cass Tech building, an abandoned school in Detroit (the photo shown above is what Cass looked like when two friends and I explored it last summer; most of it has since been torn down). Two readers have helped shed a bit of light on this.

First, Erik Shmukler found the original 1929 Michigan law that served as the basis for the anti-fraternity statement, along with a 1930 court case that affirmed its constitutionality. Here's his summary of his findings:

The brief synopsis of the reasoning behind the law is that these organizations [i.e., fraternities and such] were considered disruptive to the educational atmosphere of public schools. I was hoping for some amazingly worded stuff that referenced some kind of sensational crime wave perpetrated by marauding gangs of high school frat boys, but alas, I can't find anything other than what seems to be a bunch of adults concerned that kids wouldn't pay attention in school.

It seems that the biggest change since 1929 is that the onus is now on the school officials to make sure there are no secret organizations, as opposed to penalizing kids for joining them. I'm trying to connect the dots between 1929 and the present day in terms of changing the focus from kids to the adults, but I'm having trouble filling that in.

Interesting. You can see the original law and excerpts from the court case -- all of which Erik copied and pasted from Lexis-Nexis -- here.

In addition, Chris Powers turned up a 1956 issue of the National Association of Secondary School Principals Bulletin that includes a 12-page article about secret societies in public schools. Unfortunately, the article costs $25 to view -- too steep for me. But if anyone out there feels the urge, let us know what you find.

Big thanks to Erik and Chris for their contributions -- much appreciated.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, the Manhattan Trade School for Girls had a job placement office that helped the students find work after they graduated. When a student was placed in a new job, she was given postage-paid postcard, which she was expected fill out with a description of her experiences at the job and then mail back to the placement office. The information on the postcard was then transferred to a beige card in the student's permanent file.

Those beige cards had extremely small boxes, which forced the placement office's staff to execute some extraordinary handwriting. In the case of Sarah Aboulafia, whose main report card is shown above, the data on the beige card is a model of teeny-tiny space-efficiency. That image shows the card at its actual size (5" x 8"); here's a larger view, so you can actually read what was written.

There's something very physical -- almost textural or tactile -- about this handwriting. It was done with a fountain pen, but there are no smudges, no ink splotches. No cross-outs, either. In fact, there are only two or three cross-outs in my entire collection of Manhattan Trade report cards, which really speaks to the quality of penmanship during the early 1900s (or maybe just to the incredible level of schoolmarm-ish perfectionism among the school's staff).

A few notes about the information on Sarah's beige card:

• In the "Firm" column, it's amazing to see how they managed to squeeze in the address for each company Sarah worked for. None of those businesses still exists today (unsurprising, since the Manhattan garment trade is now a bare sliver of what it was in the early 1930s).

• The "Business" column shows all the different types of products Sarah worked on: men's neckwear (i.e., ties), nurses' uniforms, curtains, bedspreads, hats, underwear, capes (I love that it specifies evening capes), corsets, and abdominal belts (I think this means trusses).

• In the "Kind of Work" column, "Singer op" means Sarah was doing garment work on a Singer sewing machine. This is what she'd been trained in -- if you go back and look at her main report card at the top of this blog post, you'll see "Gar Op" in the top-right corner, which means her chosen trade was sewing machine operation. (Other choices offered by the school included dressmaking, millinery, lampshade making, etc.)

• As you can see, Sarah's weekly wages more than doubled in the span of about a year and a half -- a testament to the skills she learned at Manhattan Trade.

• In the "How Found" column, "MIHS" refers to Manhattan Industrial High School, which is what Manhattan Trade renamed itself in 1930. (It would change names two additional times in the next 15 years or so. But for the purposes of this project, I've continued to refer to its as the Manhattan Trade School for Girls, because it's less confusing for everyone if I stick to one name.)

• In the "Reason for Leaving" column, "Slack" does not mean Sarah was a slacker. It refers to a business's slack season -- the slow period in a seasonal or cyclical industry.

Amazing stuff, no? I don't know who filled out this card, but let's all give a silent thanks for her remarkable handwriting, which allows us to glean so much information nearly 80 years after the fact.

Sunday, August 21, 2011

When I decided to track down some of the families of the Manhattan Trade School students whose report cards I'd found, one of my biggest concerns was how people would respond to negative or personal information about their loved ones. After all, just about everyone's student record includes some embarrassing information, and some of the comments and notations on the Manhattan Trade cards were particularly harsh and personal. How would people respond when they saw these comments about their mother (or aunt, or whatever)? And how would I handle such situations when interviewing these people?

The student who epitomized these concerns was a girl named Tessie Karapura, whose card is shown above. Here's a larger view -- take a look at the bottom. As you can see, it reads, "Irregular menstruation (no pain). Dr. says girl will outgrow this."

There was good reason for the school to have made this notation. Irregular periods can be a sign of malnutrition, and many of the Manhattan Trade students came from impoverished families, so diet and nutrition were a constant concern. Nonetheless, this seemed like a very personal detail for me to know about.

But that's nothing compared to a note that appears later in Tessie's file, where a school administrator wrote, "Walks around as if she were dying. Absolutely pepless." Pepless! It would be amusing if it didn't seem so devastating. Between this comment and the menstruation note, I wasn't in any particular hurry to sit down with Tessie's descendants.

When I started trying to find students' families, I didn't go about it with much rhyme or reason. I was lucky enough to have a small army of research volunteers assisting me, so I pretty much just typed up a list and said, "Okay, you look for these five students' families, and you look for these five, and you take these five…" and so on. I knew it would be difficult research (Manhattan Trade was a girls' school, so almost all the students had presumably gotten married and changed their names), so I figured I'd just follow leads as they came in.

If this were a movie, the first family to be located would be Tessie Karapura's. Fortunately, this is real life, so that's not what happened.

Instead, hers was the second family.

One of my volunteers had located Tessie's brother. And I couldn't just not follow up on the lead -- for all I knew, we might not find any additional families. But man, why did we have to hit paydirt on this particular student right at the beginning of the project? I imagined myself going over Tessie's report card with her brother: "And yes, apparently your sister had irregular periods as a teen…" Ugh.

I reluctantly called Tessie's brother, who was in his 80s and living in New Jersey (Tessie herself had died several years earlier). He seemed a bit confused by my inquiries but agreed to meet with me at a coffee shop near his home. I mailed him copies of Tessie's student file and prepared to meet with him a few weeks after that, but then he called and said I'd be better off contacting his niece and nephew -- Tessie's daughter and son, respectively -- because they would have more to say about her. He gave me their contact information and said goodbye. I'm still not sure why he changed his mind about meeting me. Had he found the information in Tessie's file distasteful, or was he just uncomfortable with the whole notion of discussing family matters with a stranger? Maybe a bit of both.

I followed up with Tessie's daughter and son. Both of them were polite and gave me some perfunctory information about Tessie, but neither one seemed eager to meet with me or even be interviewed over the phone. Given my own reservations about some of the content in Tessie's file, I decided to put her in the "Well, I did what I could" category and move on.

Happily, most of the other families I've contacted during the course of Permanent Record have been remarkably generous-spirited about meeting with me. There have been a few tense moments about some of the material in the report cards, but they've all been handled with grace and humor.

As for Tessie, she had enough "pep" to raise a family, which seems like a good rejoinder to that comment in her file.

Thursday, August 18, 2011

The photo you see above is from the 1952 yearbook of the Manahattan Trade School for Girls (it was actually called Mabel Dean Bacon Vocational School by that point, but it was essentially the same school). It shows the school's third and final home, which opened in 1918 and still stands today on the corner of Lexington Avenue and 22nd Street in Manhattan. It has been a 6-12 school since 1992, but the original "Manhattan Trade School for Girls" lettering is still plainly visible on the façade.

But this building is not where I found the Manhattan Trade School report cards. I found them in a different school -- the old Stuyvesant High School, on East 15th Street. (I'll explain what I was doing there, and how the cards ended up there, in the Slate series next month.) And as it turns out, these two school buildings -- Manhattan Trade and Stuy -- were designed by the same architect, a fellow named C.B.J. Snyder.

I don't know much about architecture, and I'd never heard of Snyder, but he appears to have been an interesting guy. According to his Wikipedia page, he served as the city's school buildings superintendent from 1891 through 1923, during which time he designed over 400 structures (Stuy and Manhattan Trade were both built during this period), several of which are now city landmarks and/or on the National Register of Historic Places. Along the way, he pioneered a number of design innovations.

Snyder supposedly "preferred [to build schools at] mid-block locations away from busy and polluted avenues." He wasn't able to do that with Manhattan Trade, which sits right on a heavily trafficked corner. But the 10-story building is now nearing its 100th birthday and has been continuously occupied as a school the entire time, which seems like a fair measure of success.

New York Times metro columnist Jim Dwyer wrote a really nice piece about Snyder a few years ago. If anyone knows more about Snyder's work, I'd love to hear from you.

Wednesday, August 17, 2011

I didn't set out to become a report card collector, specializing in student records from old vocational schools, but that's what's happened. In addition to the 395 Depression-era files from the Manhattan Trade School for Girls, I also stumbled across a small stash of 1950s report cards from Cass Tech, a vocational school in Detroit. (I'll explain how I found the Cass Tech files -- and will give further info on how I found the Manhattan Trade cards -- in the Slate series next month.)

By and large, the Cass Tech files aren't as interesting as the ones from Manhattan Trade -- with one exception. Each Cass Tech student record includes a "Non-Fraternity Membership Statement" like the one shown above (here's a larger view, so you can read it). It cites a 1929 state law that prohibits

any organization [in the public schools] whose active membership is composed wholly of chiefly of pupils in the public schools of this state and perpetuating itself by taking in additional members from the pupils in the public schools on the basis of the decision of its membership rather than upon the right of any pupil who is qualified by the rules of the school to be a member of and take part in any class or group exercises…

In short: Don't join a private club that excludes other kids. But if such groups were already banned, why was it necessary to make the students -- and their parents! -- sign a promise not to join them? And why was the ban enacted in the first place? Was it just to ensure that all kids would have equal access to school activities, or was there something larger at work? (If the law had been enacted in, say, 1952, it would be easy to view it as an outgrowth of McCarthyism. But it was enacted back in 1929, which doesn't seem like a particularly anti-secret society period.)

I've spoken to one Cass Tech student from this period (not the one whose signed form is shown at the top of this entry), and he had no memory of any of this. I've also tried Googling the statute in question -- the Public Acts of Michigan of 1929, Section 7664 -- to see if I could glean any legislative history, but I came up empty.

If anyone from Michigan knows more about this, I'm all ears.

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

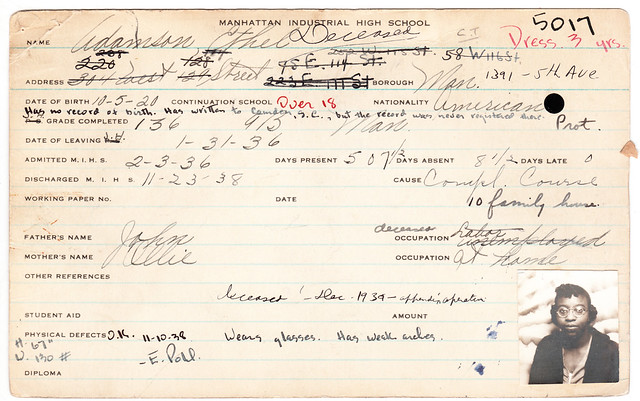

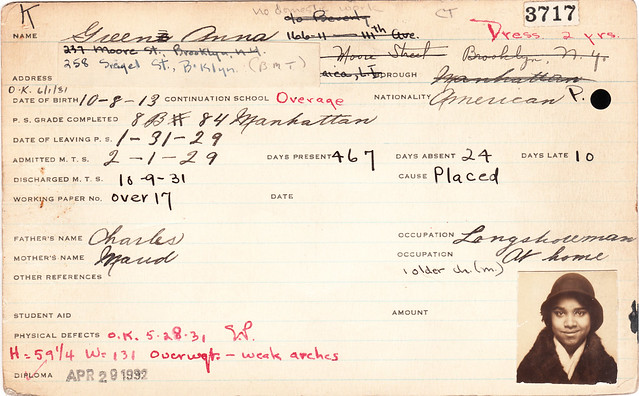

You may have noticed that Anna Green, who I wrote about a few days ago (she's the one who ended up drawing the short straw in a bankruptcy settlement), had a black dot on her report card -- a dot very much like the one that appears on Ethel Adamson's card, which is shown above. You may also have noticed that Anna and Ethel were both black.

This is no coincidence. Only about 5% of the Manhattan Trade School report cards in my collection are from black students, but they all have this small, adhesive black dot. The dot also appears on the card of a Native American student, and a Hispanic student was given half a dot. So the dots were apparently used for all students of color.

You've heard of the term "a black mark on your record"? Here it is, literally.

I initially thought the black dots were meant to stigmatize the students in some way (like a scarlet letter, or a concentration camp tattoo), but I eventually figured out a more benign reason for them. I don't want to give everything away, so I'll explain this more fully in the Slate series; for now, take my word when I say I don't think the dots are as offensive as they initially appear to be.

Sunday, August 14, 2011

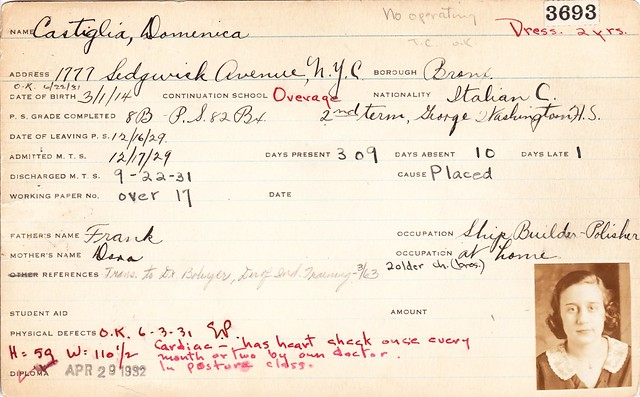

One of the most interesting aspects of the Manhattan Trade School report cards is that the cards list the names and occupations for the students' parents. In the case of Domenica Castiglia, whose card is shown above, her father was a "ship builder-polisher" -- a profession that no longer exists in New York City.

To skim through some of the other parents' occupations is to get a glimpse of a city that few living New Yorkers can remember, or even imagine: soap maker; ice and coal deliverer; stableman; cigar maker (sometimes engaged in by both parents); twine and rope maker; sheep butcher; organ grinder; farmer; "picking hairs" (literally, a nit-picker -- someone who treated people afflicted with head lice); and so on.

My favorite of the bunch is listed on the card of a student named Caroline Cataudella, whose father, George, was listed as a "macaroni laborer" -- in other words, he worked in a pasta factory. Of course, pasta manufacturing still takes place in New York today, so this isn't some quaint bygone trade, but there's something really endearing about the term macaroni laborer (or, even better, macaroni labor, which is what was originally written on the card before someone added the "er" at the end).

As it turns out, George (whose real name was Giorgio) didn't just "labor" at macaroni -- he had his own company, the Harlem Macaroni Mfg. Co. I learned this simply by Googling "cataudella macaroni," which led me to a book called The Journey of the Italians in America, which features this photo. According to the caption, the photo was taken around 1934 -- about seven years after Caroline attended the Manhattan Trade School. Note that the address listed in the caption and on the side of the truck -- 239 E. 108th St. in Manhattan -- is the same one shown on her report card.

Thursday, August 11, 2011

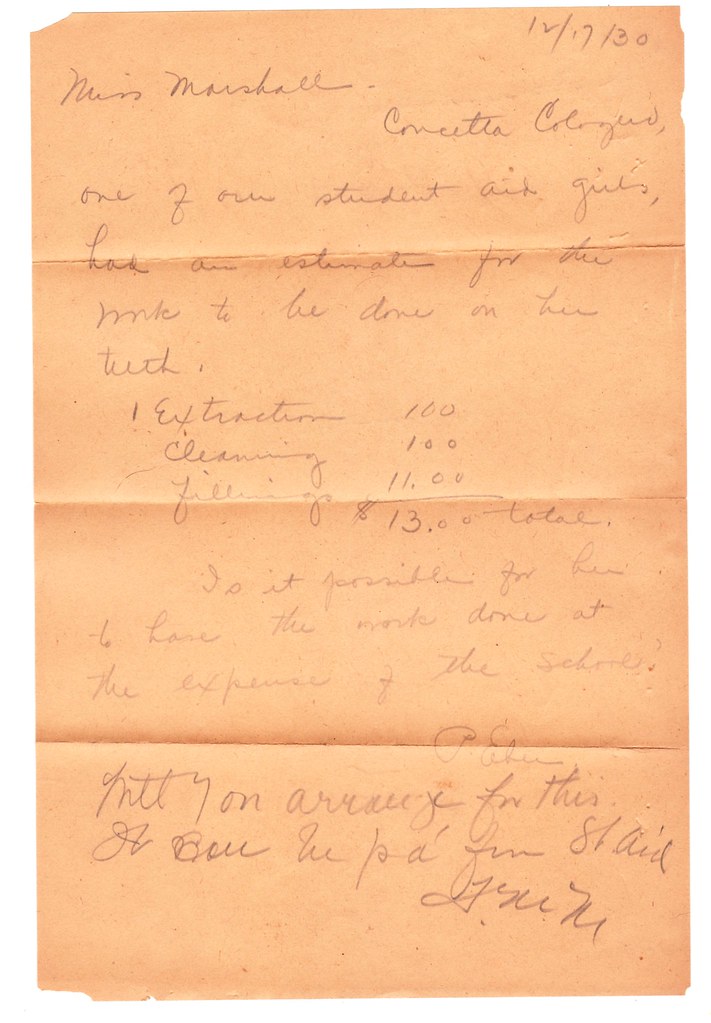

Most of the 395 student records in my collection are fairly extensive, with four of five individual cards, most of them filled out on both sides, plus assorted additional paperwork. But some of the files are incomplete, and a few of them are barely files at all. The letter you see above is all I have for a student named Concetta Colozou -- that's the entirety of her "file."

As you can see, Concetta was receiving student aid (the Manhattan Trade School for Girls made a small weekly stipend available for extreme hardship cases) and was facing a series of dental procedures she could not afford. The letter was written by one of the school's employees -- it's not clear to me whether it was a teacher or another staff member -- and was addressed to "Miss Marshall." That would have been Florence M. Marshall, who was the school's principal from 1911 through 1937. (That photo is from an old yearbook.) Her response, written at the bottom of the letter, reads, "You arrange for this. It can be paid from student aid."

The report cards are full of paperwork like this. Letters from social workers and doctors, letters from parents, letters from the school to the students -- a treasure trove. More of them will be shown in the Slate series next month.

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

Before we get to today's post, one quick order of business: I've taken the first entry on this blog and repurposed it as an "About Permanent Record" page. That page, along with the full list of all 395 students whose report cards I have, is linked in the right sidebar.

Now then … The Manhattan Trade School for Girls was unusual because it had a job placement office that helped the girls secure jobs (mostly garment-related, because most of the students were trained in sewing or dressmaking) after they graduated. The girls and the employers were encouraged to report back on each other, and all those reports were documented in the students' files. This information is some of the most compelling material in the report cards, because you can see little dramas and storylines playing out.

One such story involved Anna Green, a dressmaking student who attended Manhattan Trade from 1929 through 1931 (the front card of her student record is shown at the top of this page; you can see the rest of her file in this slideshow). Anna faced a lot of challenges: Her mother had left the Green household when Anna was four. When her father, a longshoreman, had trouble finding work during the Depression, he could no longer provide for Anna and sent her to live with friends. The school found some positions for her, but her stint at a blouse and scarf manufacturer called E. Vonder Esch just compounded her problems, as seen in this series of exchanges she had with with school's job placement director:

May 3, 1933: Vonder Esch out of business and owes employees three weeks salary. Attorney already on the case.

Oct. 31, 1933: Received a check for $1.73 for my services at Vonder Esch. Can you give me some information on this?

Nov. 2, 1933: You may get more from the Vonder Esch bankruptcy. It depends on what they realized from the sale of the business. Why don't you communicate with the attorney?

Dec. 6, 1933: Earn $25 a month. Five dollars of this each week has to be contributed at home, and the rest is used up for carfares. This leaves almost nothing for clothes. Home conditions are unbearable and will continue to be so until I can give more. Mrs. Schachter [Anna's employer at the time] has refused me a raise, saying she cannot pay any more. Shall I look for a job now or after Christmas?

Dec. 8, 1933: Stay with Mrs. Schacter for the present. There are no jobs now.

Dec. 13, 1933: Telephoned attorney Baer regarding the remainder of the back salary due me from Vonder Esch. Was informed that I had received my share of the Vonder Esch estate. Feel as if I've been cheated. How can I find out if this was a just settlement?

Dec. 15, 1933: I told you before how bankruptcy cases are settled. I'm sure there is no fraud here. It simply means that, after settlement, there was very little to divide among the creditors.

The school continued to find jobs for Anna for the next four years. I wasn't able to locate her family, so it's not clear what happened to her after that.

The report cards are full of unresolved stories like this one. Many more of them will be presented in the series of Permanent Record articles that will appear on Slate next month.

Monday, August 8, 2011

The short version: My name is Paul Lukas. Fifteen years ago I came upon a discarded file cabinet full of incredible 1920s and ’30s report cards from a defunct girls' vocational school. I took as many of the cards as I could carry and then spent the next decade-plus wondering what to do with them. At some point in 2009 I decided to track down some of the students -- or, since most of them were likely deceased, their families -- and see how their lives had turned out. I've spent much of the past two years doing that. This has led to, among other things, numerous instances of calling people up and saying, "Hi, you don't know me, but I have your mother's report card from 1929. Would you like to see it?"

The result is Permanent Record, a five-article series that will be running on Slate during the week of Sept. 19. It will tell the stories of some of the students whose report cards I found, the remarkable school they attended (it was called the Manhattan Trade School for Girls), and my own experience connecting the dots between the cards and the students' families.

I plan to use this blog to address issues that aren't covered in the Slate series, to post some material that was originally written for the series but ended up on the cutting room floor, to provide follow-up coverage of developments that take place after the series is published, and so on. My current plan is to do short posts every two or three days, although one thing I've discovered over the past few years is that Permanent Record is a very fluid, evolving project, so there's a decent chance that my initial plans will have little bearing on how this blog eventually turns out.

Anyway. Want to know if a loved one or acquaintance is represented in my report card collection? You can browse the complete list of all 395 students here. Have questions, suggestions, or feedback? Contact me.

More soon.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)