Click to enlarge

On the left is a Victorian-style photo portrait; on the right, an illustration based on the photo, which was done by a Brooklyn artist named Lauren Simkin Berke.

Berke has a very Permanent Record-ish project called To Be Kept, which goes like so: She obsessively collects old photographs from flea markets and antiques shops (some of them Victorian portraits like the one shown above, but also 20th-century snapshots not unlike the ones I recently blogged about) and then creates drawings based on them -- about one per weekday, which she's been posting on her blog since 2006. Some of these pieces ended up in a gallery show last winter, and now she's running a Kickstarter campaign so she can publish a To Be Kept book.

Berke's Kickstarter page has a nicely worded explanation of why she finds these old photos so compelling:

I find it strange that these documents are for sale as part of a consumer marketplace, instead of being in albums on bookshelves in the homes of the families of those in the photos. I find myself at the intersection between a fascinated voyeurism and a determination to know these documents as well as humanly possible in order to give them a new, longer life.

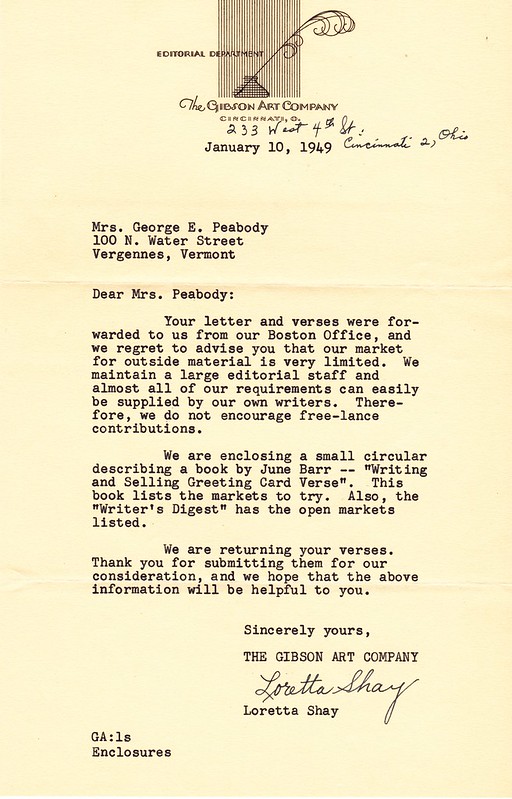

When I learned about Berke's project, I sent her a note and basically said, "Hey, I'm into found artifacts and passive voyeurism too!" She quickly wrote back and mentioned that she'd recently acquired some old report cards from the late 1930s.

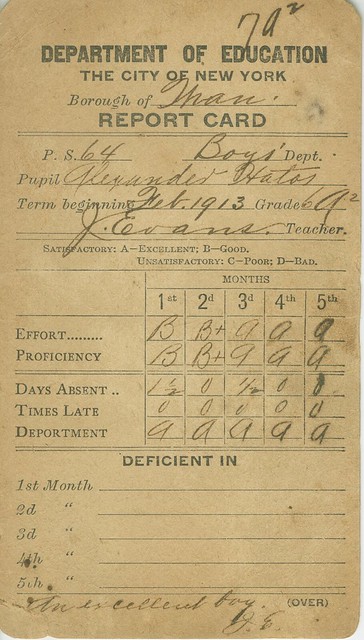

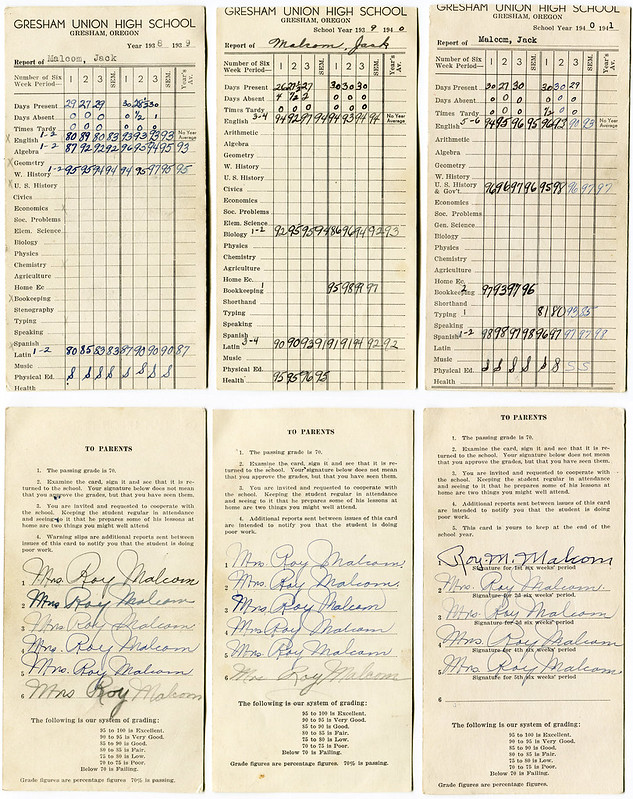

Hmmm, report cards, you say? I asked if I could have a look, and she graciously made the following scans for me (click to enlarge):

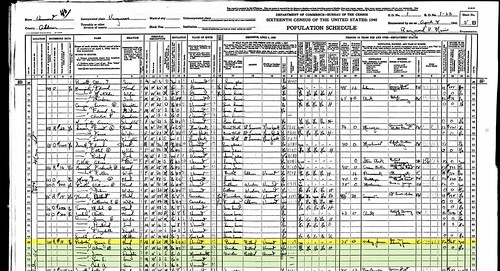

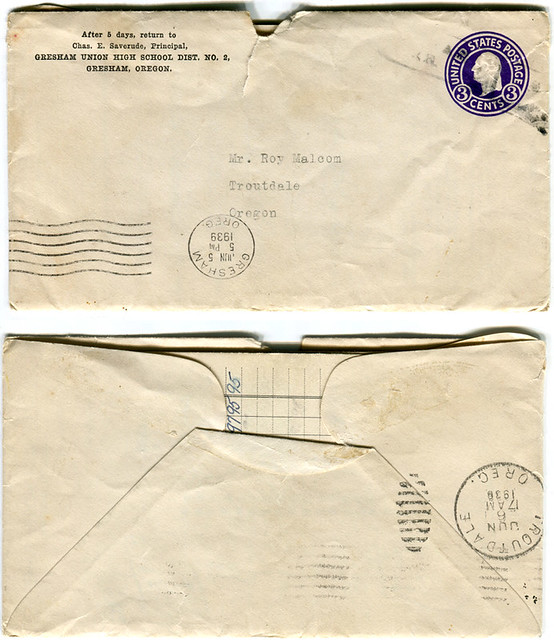

As you can see, these are three years' worth of report cards, and the envelope one of them was mailed in, for one Jack Malcom, who attended high school in Gresham, Oregon (which is just outside of Portland). Among the notable details:

• One of the subjects listed on the report cards is "Soc. Problems." Never seen that before.

• The earliest of the three cards -- the one at far left -- has an embarrassing typo, as one of the subjects is listed as "Bookeeping." This was corrected ("bookkeeping," with two k’s) on the subsequent two cards.

• As was common at the time, Jack's mother signed the cards with her husband's first name: "Mrs. Roy Malcom." Her signature has a bit of flair, which I like.

• The Malcoms lived in Troutdale, which is adjacent to Gresham and must have been a very small town at the time, because the person addressing the envelope didn't even bother to include a street address.

"I purchased the cards at a shop in Portland called Ampersand," Berke told me. "I stop in there whenever I'm in Portland, as they keep a well-stocked bin of unsorted vintage snapshots."

I was curious to know if Berke had tried to track down Jack Malcom and/or his family, as I've done with the Manhattan Trade School report cards, so I asked her. She gave a really thoughtful, interesting response, along with an intriguing story about a future project:

I did Google him. He lived in Gresham (it seems for all his life, though I'm assuming he would have served in WWII), where he was a florist. He died in 2009 at age 85. He was on the metropolitan arts commission in Portland, and left a fair amount of money to arts, educational, and historical organizations when he died.

In general, I am not trying to get items back to the family they came from. The assumption is that they are orphaned, and would not be for sale if anyone related to them were alive, or cared. In Jack's case, it seems he had no family.

Most of my work is with photographs, and not text-based ephemera. There are often fragments of text -- or in the case of Victorian studio portraits, there is often a full name and address of the photographer and/or their studio. But I have had very little luck in getting further information, even when I have a full name and address. It would likely take going to historical societies and such. For the most part, I have given up on focusing on finding these details, preferring to focus more on what there is to be seen in the images of the photographs.

When I purchased the report cards, I also purchased an unopened letter from the mid-1940s. The letter was sent from San Francisco to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and I just happened to be on my way to San Francisco myself at the time (and my best friend lives in Boston, near Cambridge). I immediately decided to wait to open the letter until I was in San Fran, and to make a replica of it and the send it to my best friend, re-creating the letter's intended journey. My friend's then-boyfriend (now ex) works at Harvard and thought he could find out if the intended recipient was alive, and if so get an address. Since they broke up, I'm not sure he's going to follow through, but I am going to find someone else who can. If the letter's intended recipient is still alive, I most certainly intend to get him a copy of the letter.

Faaaascinating! My thanks to Berke for sharing all of this and I urge everyone to please consider supporting her Kickstarter project.

(Special thanks to Kirsten Hively, who brought To Be Kept to my attention.)