For all documents, click to enlarge

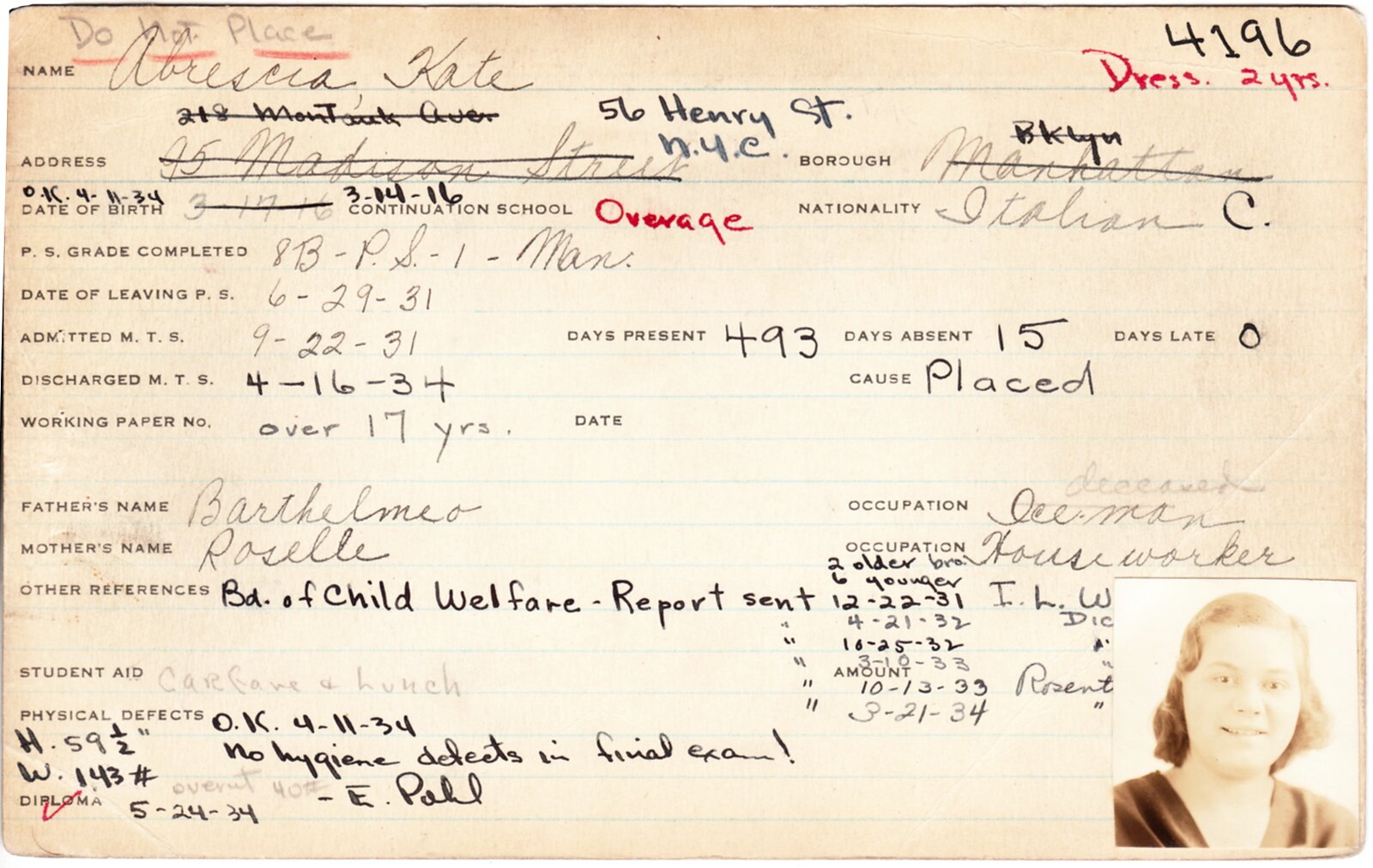

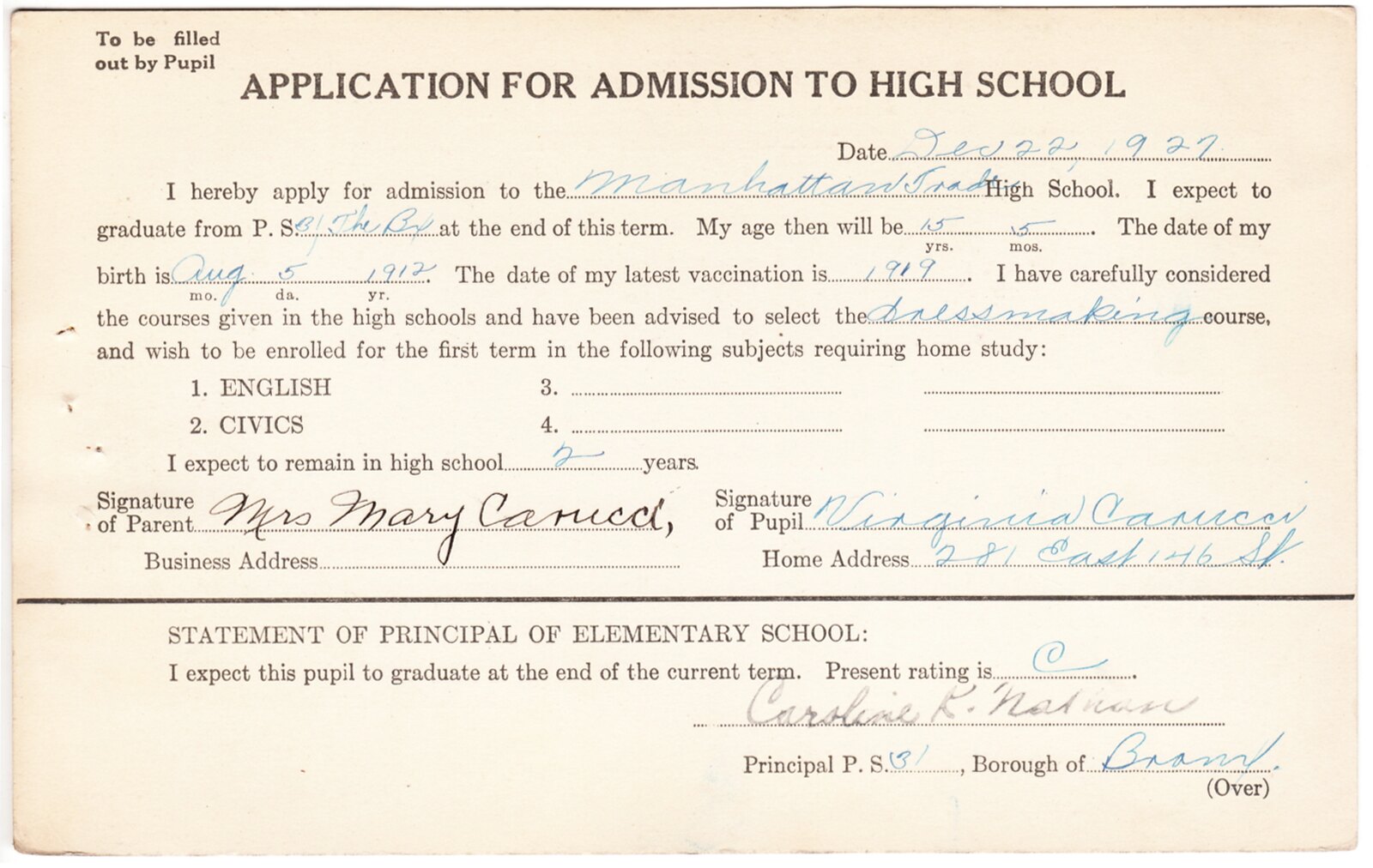

Our latest Manhattan Trade School enrollee is Virginia Carucci, a dressmaking student who took classes at the school from 1928 through 1930. As you can see above, she was part of a large Italian-American family (she had six siblings) that lived in the Bronx, where her father worked as a butcher.

Unfortunately, there's a sad note at the top: "Deceased 9-19-31." Virginia would have been only 19 at the time. We'll learn more about this later in her student record.

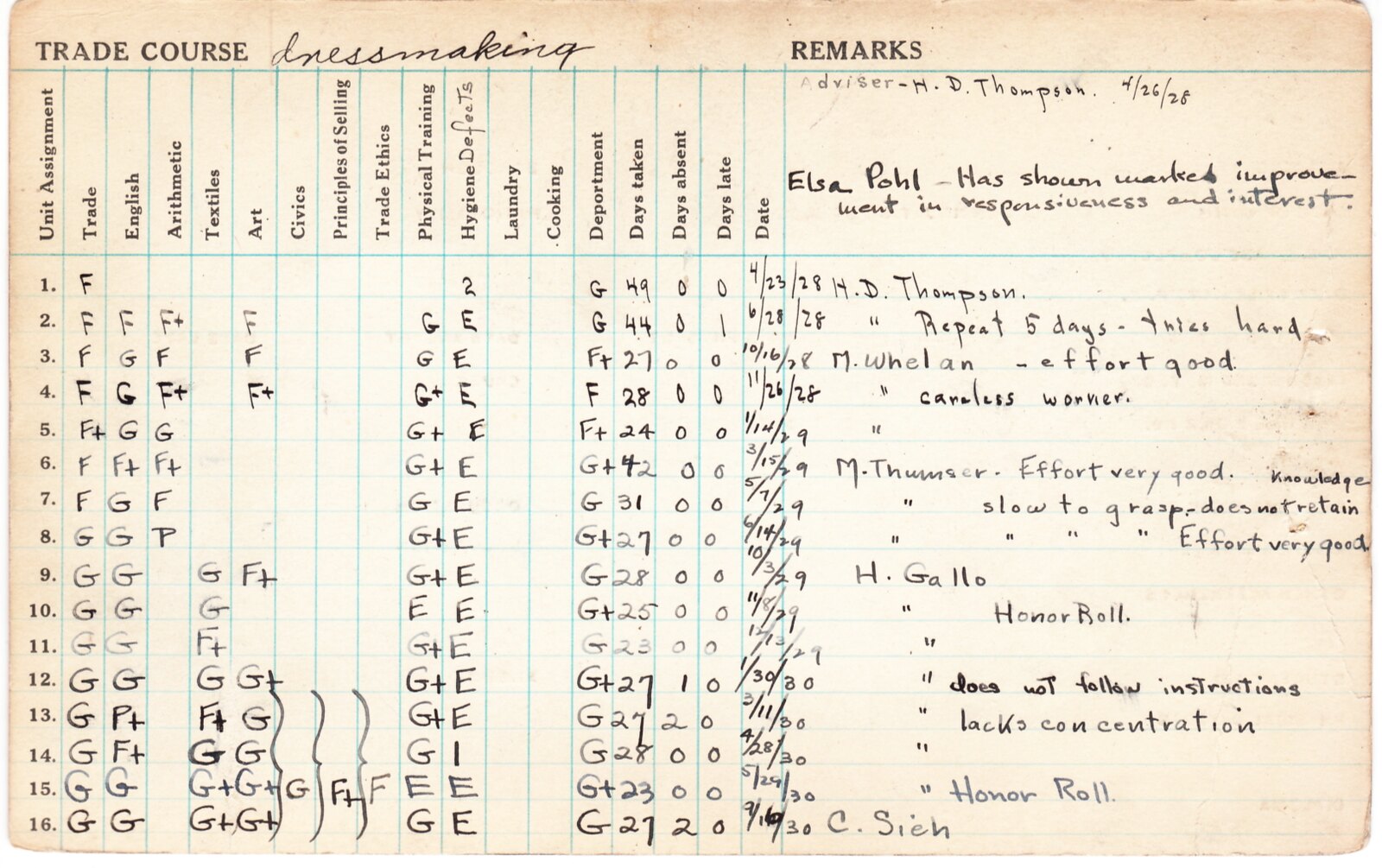

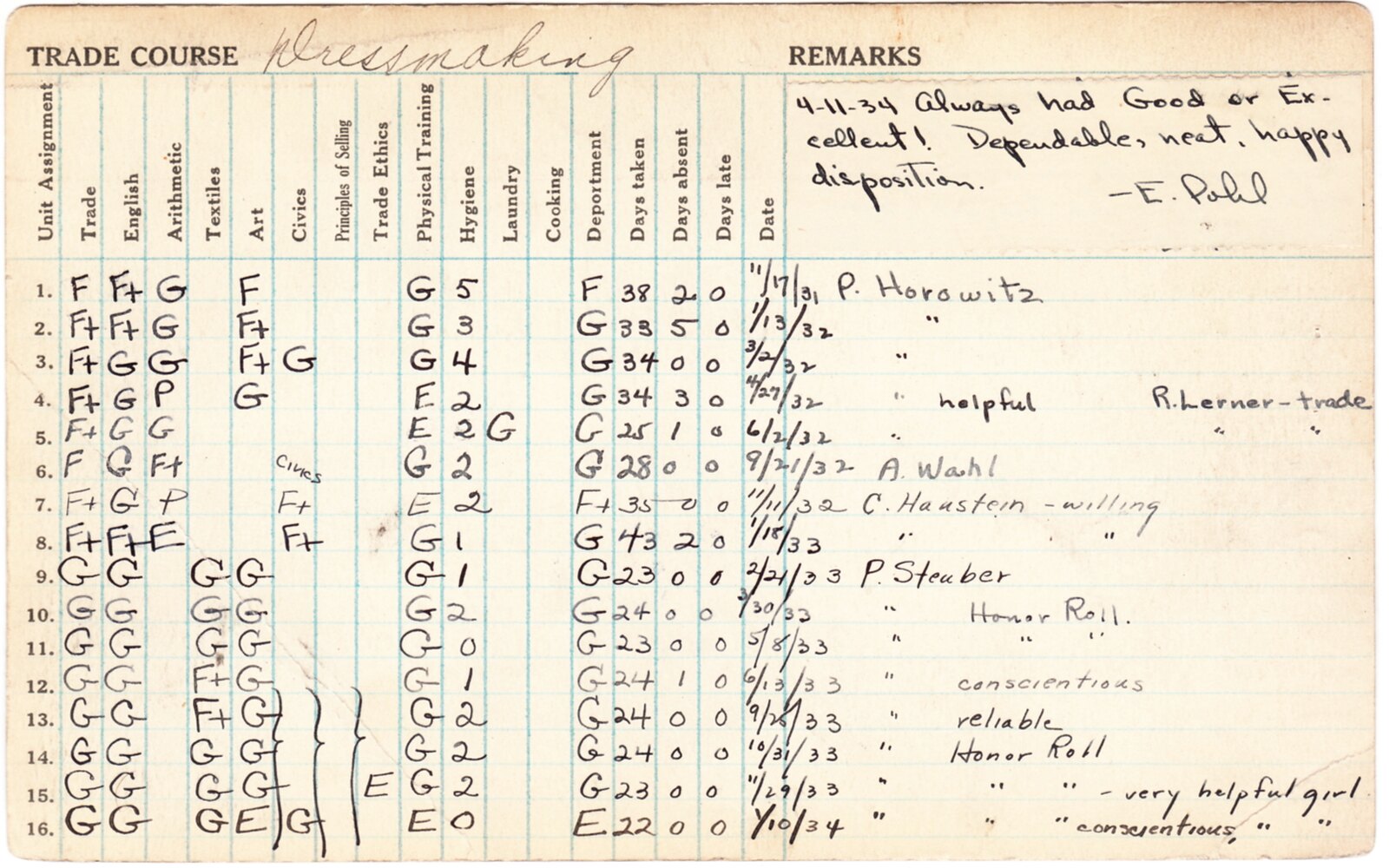

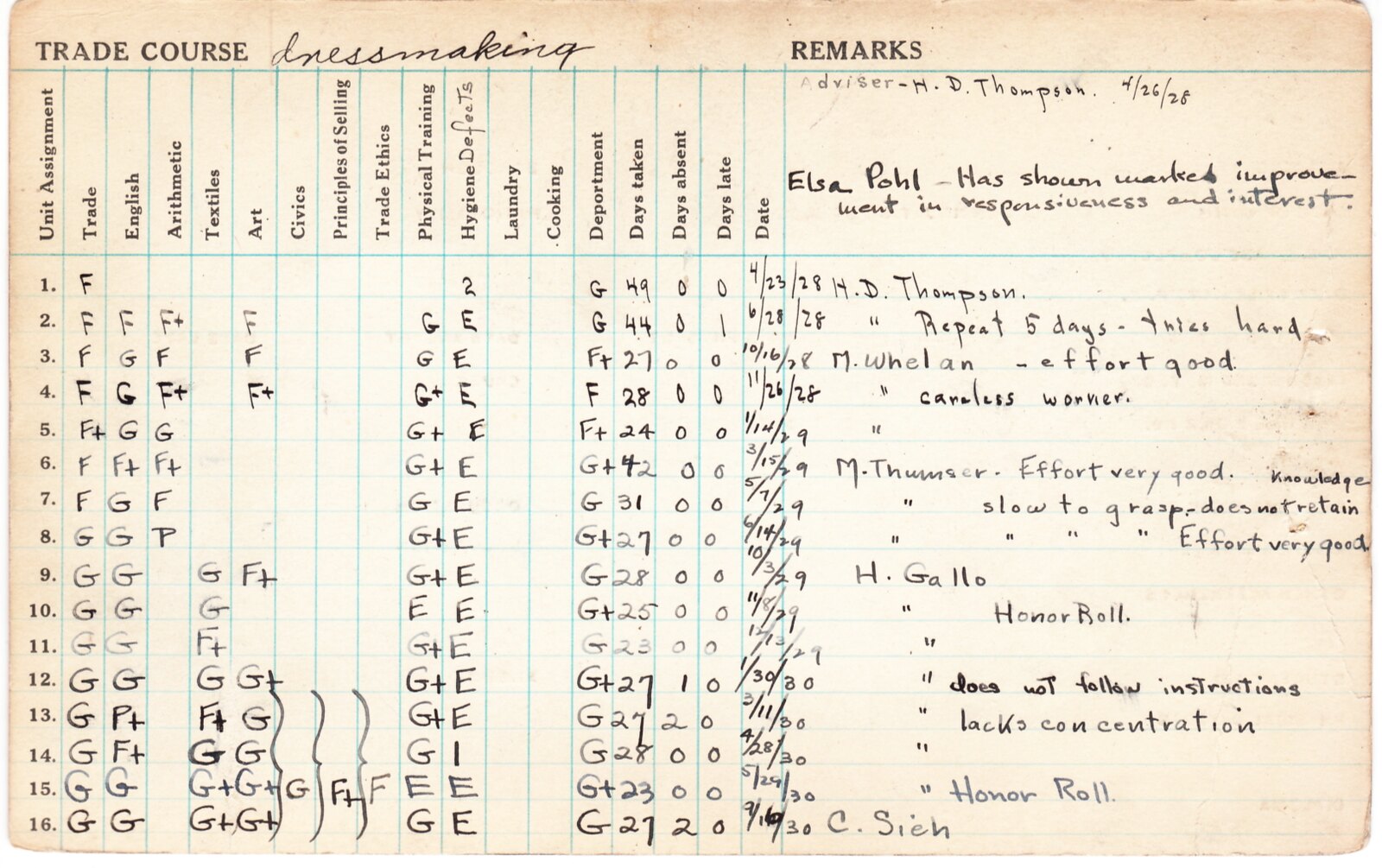

Before we get to that, let's take a look at Virginia's grades and teacher comments (as always, E = Excellent; G = Good; F = Fair; P = Poor):

As you can see, Virginia's grades were generally quite good. She made the Honor Roll several times but was occasionally called out for carelessness.

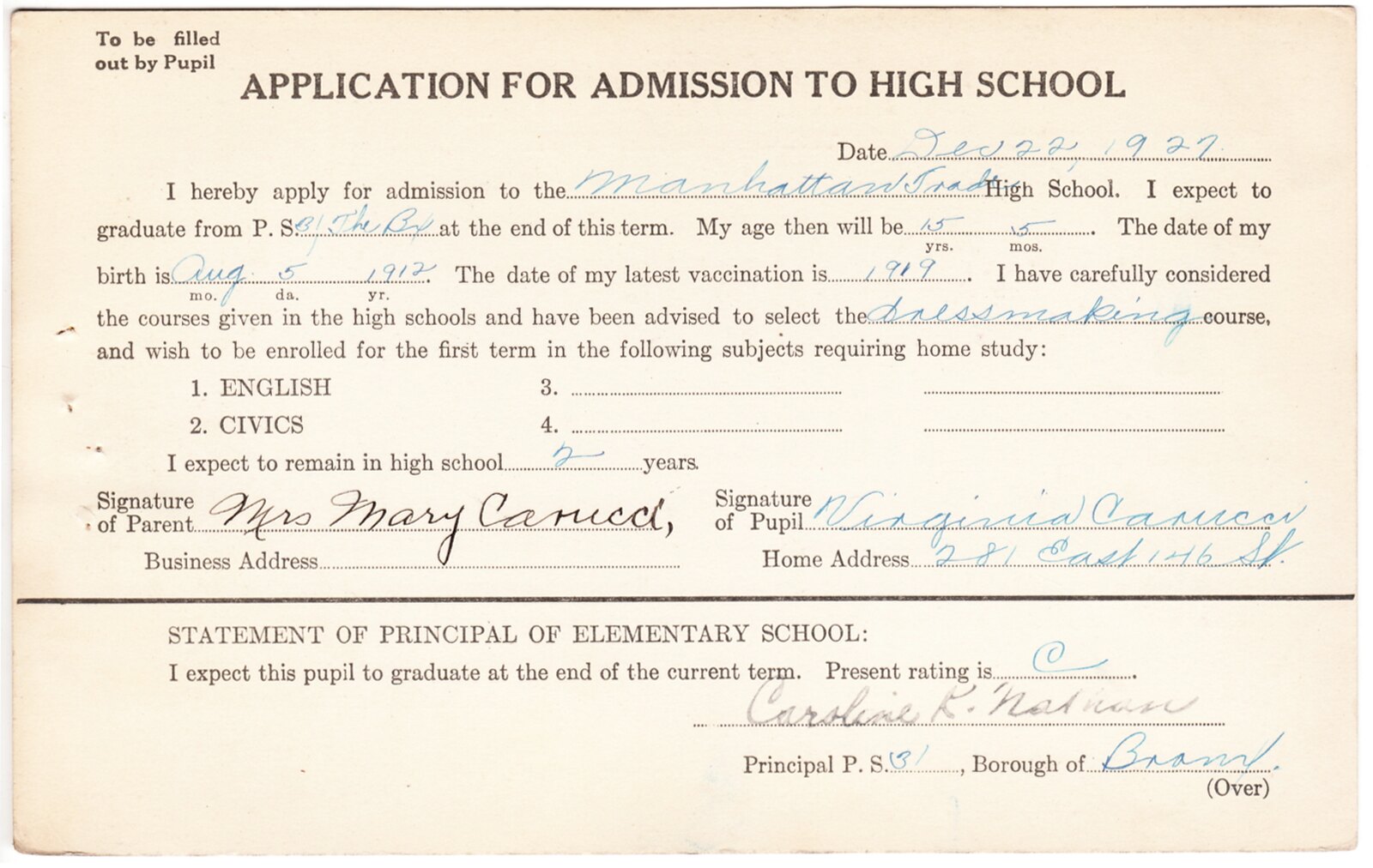

Next up is a document that I don't think I've ever shown before here on the blog: an application for admission to Manhattan Trade. For whatever reason, this card doesn't show up in most of the student records in my collection, but Virginia's was preserved in her file:

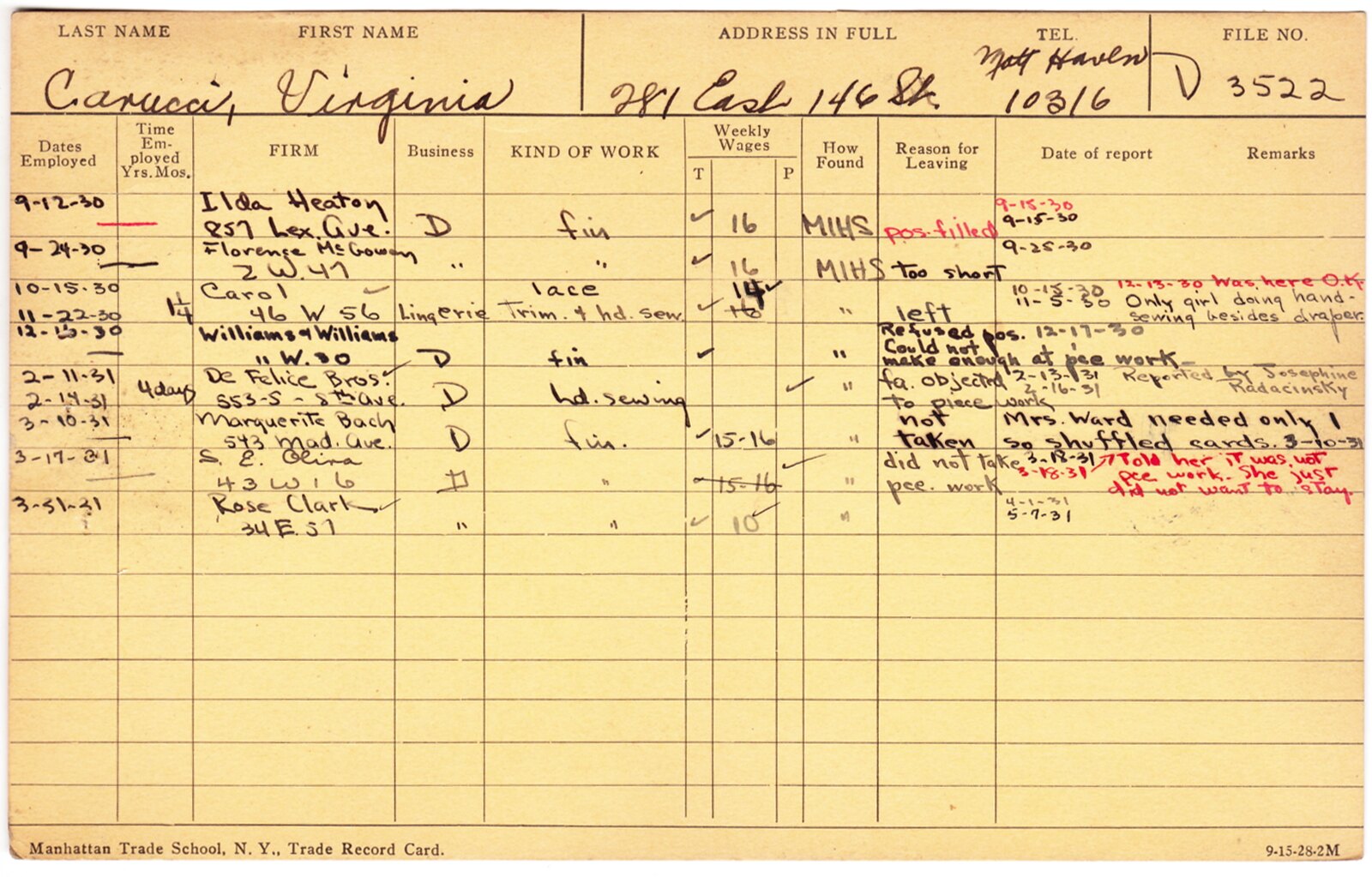

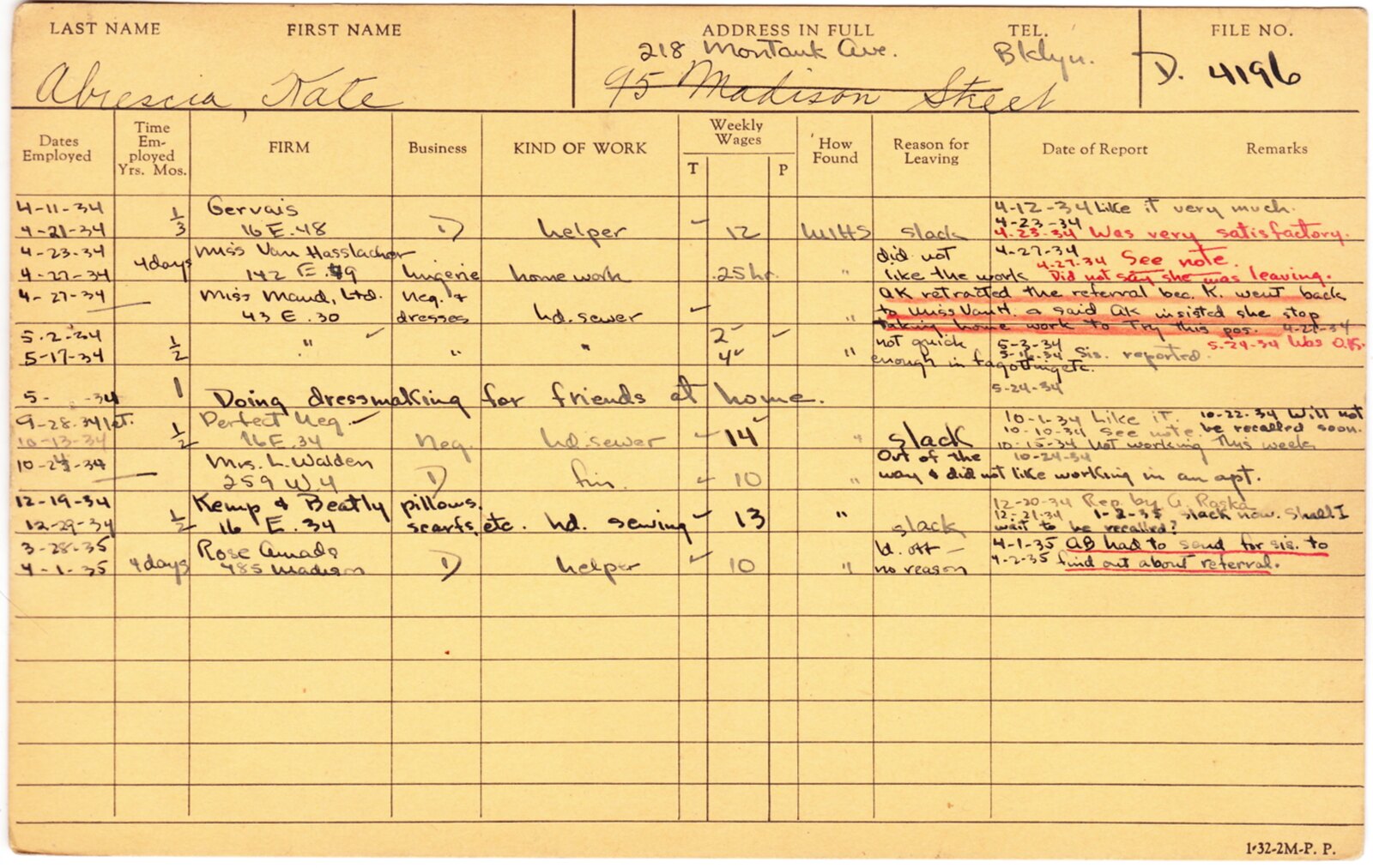

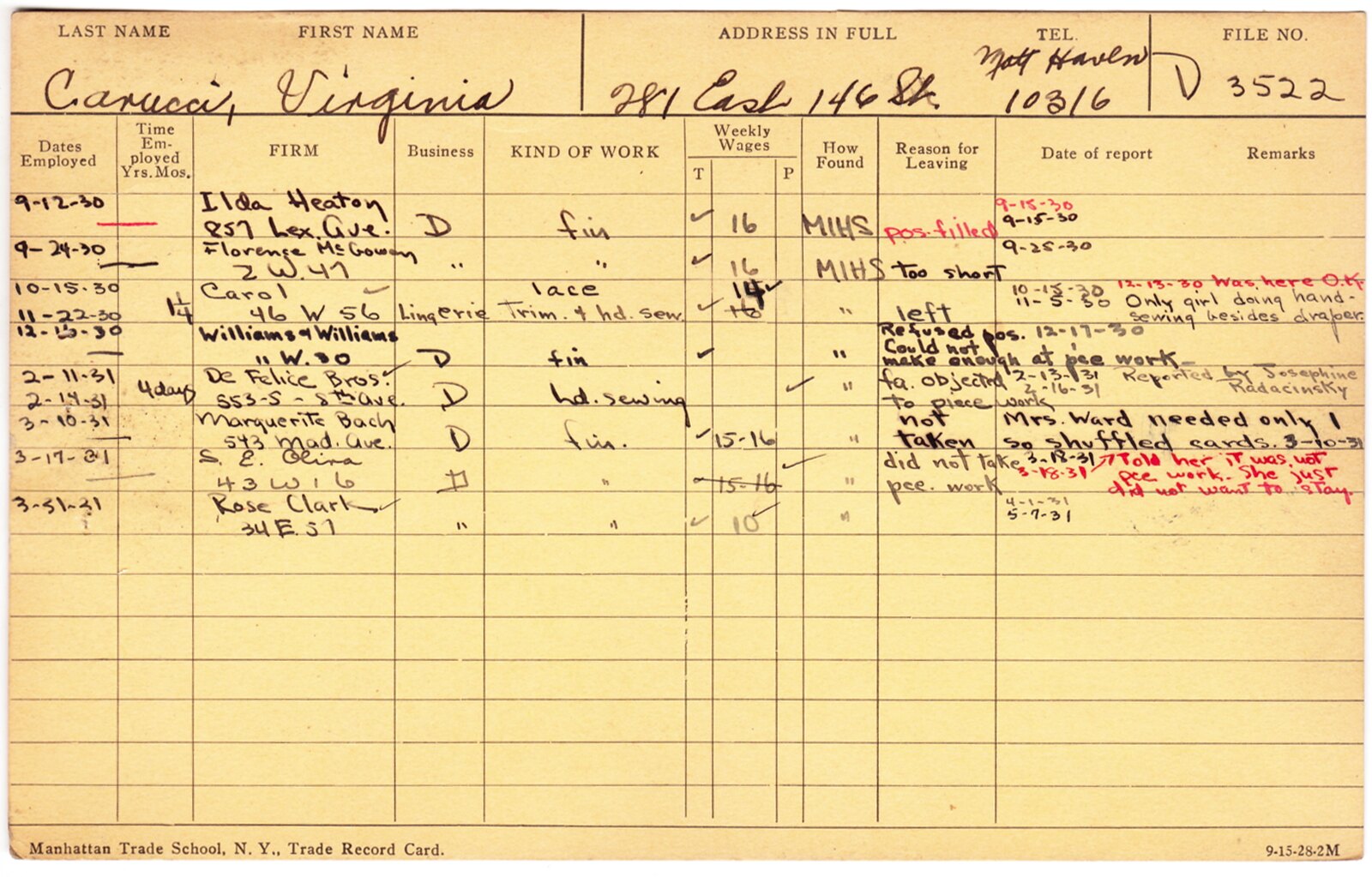

Next up is Virginia's employment record, showing the jobs to which she was referred by the school's job placement office:

There are a few interesting entries here. For Virginia's second job, for example, her "Reason for Leaving" is listed as "too short." Does this mean that the duration of the job was short, or that Virginia herself was too short to do the tasks required of her? If you scroll back up and look at the lower-left corner of the first card in her file, you can see that she was indeed short — 5'1". Hmmmm.

Virginia also left several jobs because she objected to "piece work" — in other words, being paid by the piece instead of by the week, which is a hard way to make any money for all but the very fastest workers. But in one instance, an employer (whose comment is listed in red) rebutted Virginia's claim: "Told her it was not piece work. She just did not want to stay."

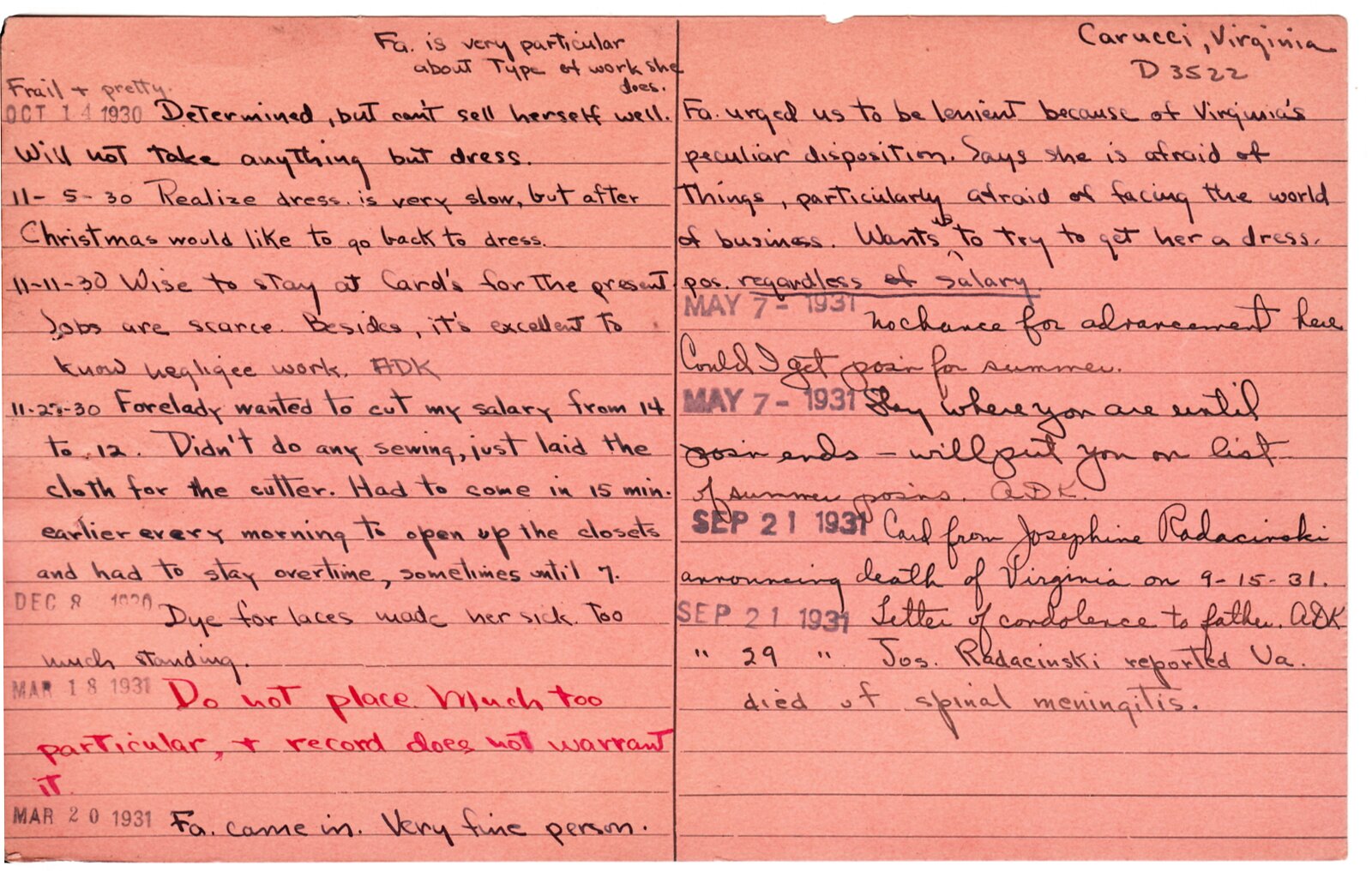

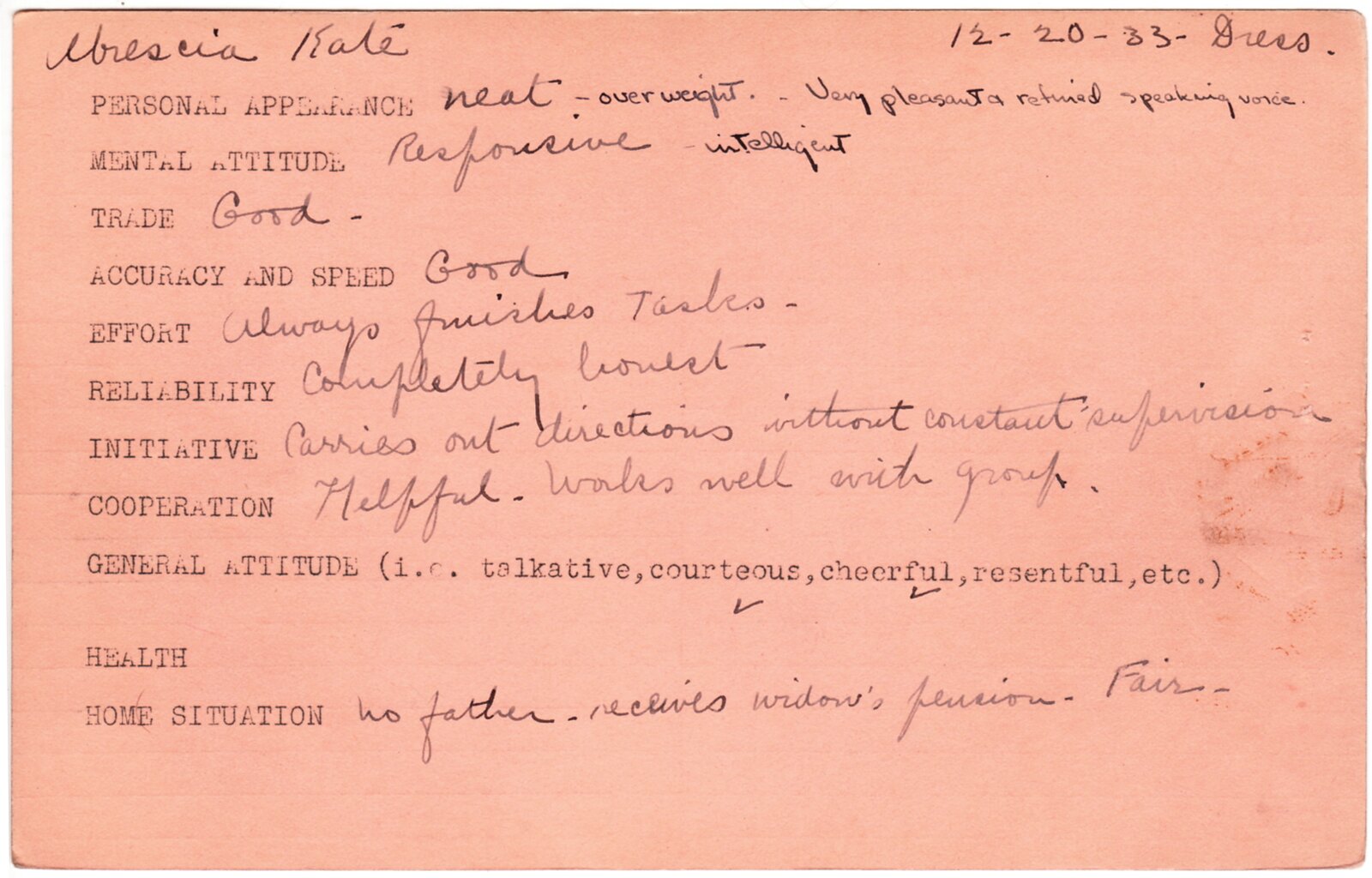

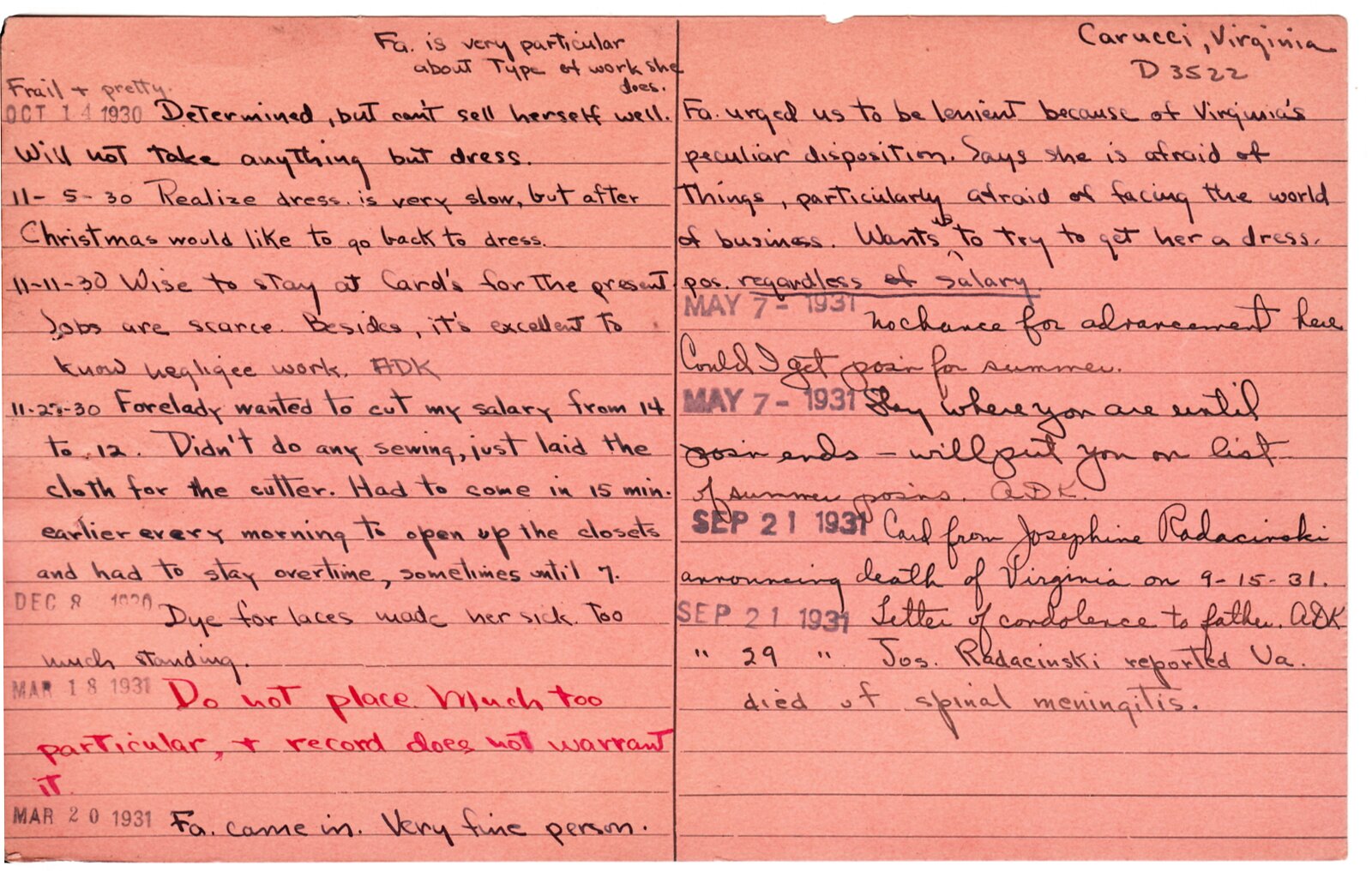

Now we come to the final card in Virginia's file, with comments from the school's job placement staff:

Lots of interesting comments on this card. Here's a transcription of some of the more intriguing bits. As usual, I've spelled out a few abbreviated and omitted terms for the sake of clarity:

Oct. 14, 1930 [comment from Althea Kotter, the placement secretary]: Frail and pretty. Determined, but can't sell herself well. Will not take [any position] but dressmaking.

Nov. 5, 1930 [comment from Virginia, who at the time was working for a lingerie shop called Carol's]: I realize dressmaking is very slow, but after Christmas I would like to go back to dressmaking.

Nov. 11, 1930 [from Ms. Kotter to Virginia]: Wise to stay at Carol's for the present. Jobs are scarce. Besides, it's excellent to know negligee work.

Nov. 28, 1930 [from Virginia]: Forelady wanted to cut my salary from $14/week to $12/week. Didn't do any sewing, just laid the cloth for the cutter. Had to come in 14 mins. earlier every morning to open up the closets. And had to stay overtime, sometimes until 7.

Dec. 8, 1930 [from Ms. Kotter]: Dye from laces made her sick. Too much standing.

March 18, 1931 [from either Ms. Kotter or another school administrator]: Do not place. Much too particular, and her record does not warrant it.

March 20, 1931 [from Ms. Kotter]: Father came in. Very fine person. Father urged us to be lenient because of Virginia's peculiar disposition. Says she is afraid of things, particularly afraid of facing the world of business. Wants us to try to get her a dressmaking position regardless of salary.

May 7, 1931 [from Virginia]: No chance for advancement here. Could I get a position for the summer? [It's not clear what job this was, as Virginia's work record shows no entries after March 31, 1931. — PL]

May 7, 1931 [from Ms. Kotter]: Stay where you are until position ends. Will put you on the list for summer positions.

Sept. 21, 1931: Card from Josephine Radacinski, announcing death of Virginia on Sept. 15, 1931.

Sept. 21, 1931: Letter of condolence sent to father.

Sept. 29, 1931: Josephine Radacinski reported Virginia died of spinal meningitis.

And that's where it ends. Interestingly, there is now a vaccine to help prevent meningitis, which seems particularly relevant given the current controversy regarding childhood vaccinations. Had such a vaccine been available a century ago, Virginia might have lived into adulthood.

• • • • •

Update: Remember Tony Trapani, the 81-year-old Michigan man who found an old letter indicating that he had a son he'd never known about? There's a sad ending to that story: A DNA test has shown that his purported son is not his son after all. Both men are devastated but say they plan to treat each other as family anyway.

(My thanks to John Chapman for alerting me to this updated info.)