For all images in this entry, you can click to enlarge

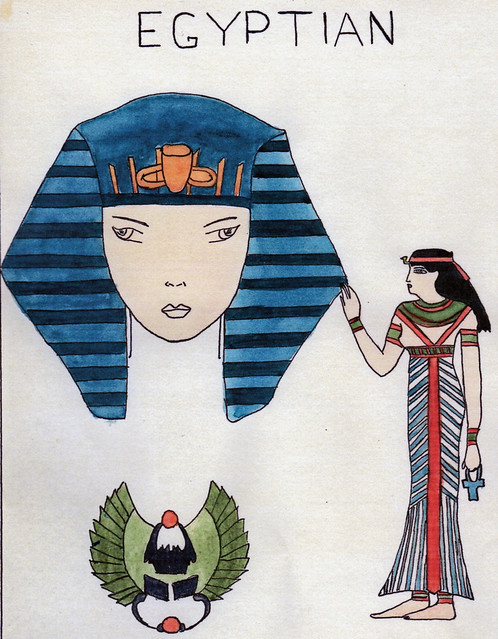

I periodically receive inquiries from people who stumble across Permanent Record while researching their family histories and want to know if I have the Manhattan Trade School report card for their mother or great-aunt or whatever.

One such inquiry recently came my way from a woman named Carol Chadwick. Carol's mother, Margaret Nagy, attended the school from roughly 1939 through 1942, when her name was Margaret Sabo. Unfortunately, Margaret's report card isn't part of my collection (almost all of my report cards are for students who attended the school from the 1910s up through the mid-1930s), but Carol asked if I'd be interested in seeing Margaret's yearbook. I said sure.

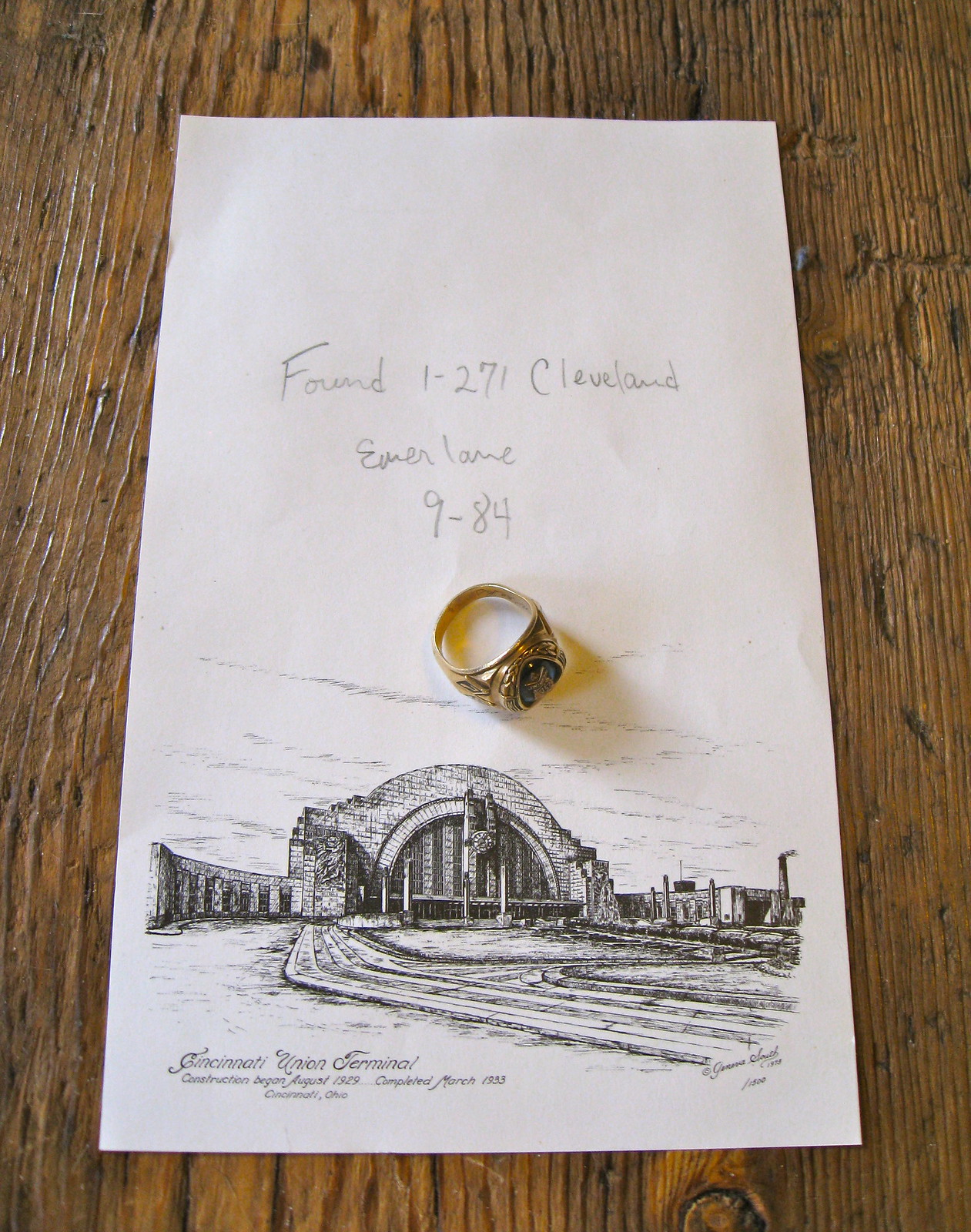

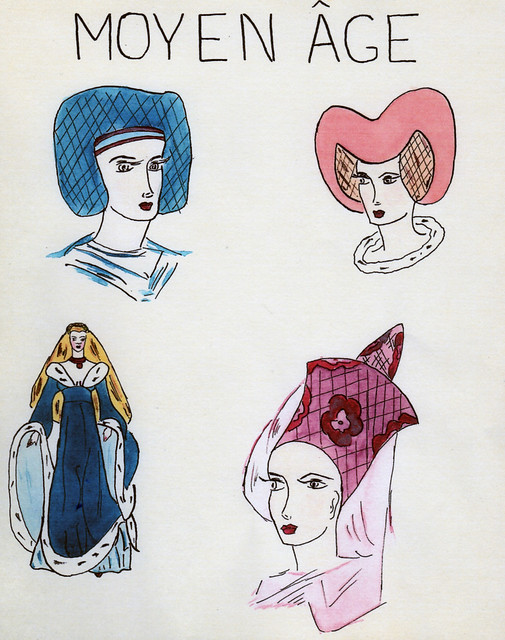

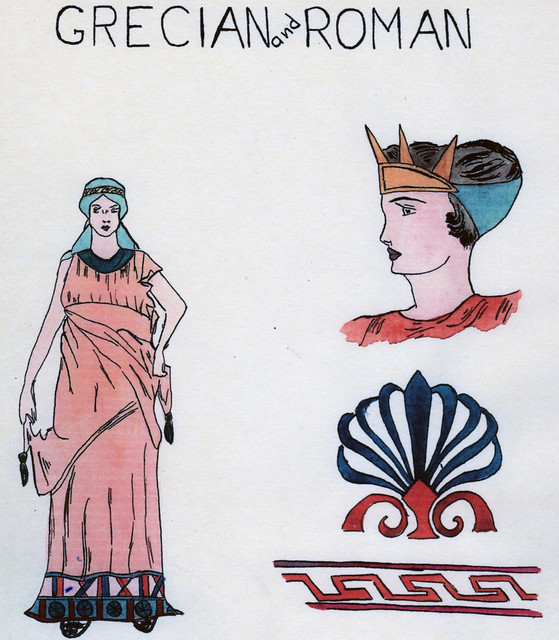

As it turned out, Carol wasn't able to locate Margaret's yearbook, but she offered me two very good consolation prizes. First, she found Margaret's art class portfolio and made printouts of some of the pages for me (you can see a few of them distributed throughout this entry). Even better, she arranged to have me do a phone interview with Margaret, who's now 90 years old.

Throughout the course of the Permanent Record project, I have interviewed only one person who attended the school as far back as the 1930s. That was Rose Vrana, who was 95 when I interviewed and wrote about her two years ago.

In Rose's case, I had her report card — she's the only living student I've found from my report card collection. But although I don't have Margaret's report card, she's still a living link to the school's PermaRec era (okay, a few years after the PermaRec era), so I jumped at the chance to interview her. We ended up speaking on the phone for about 40 minutes a few weeks ago. Here's how it went.

Permanent Record: I hope you can forgive me for beginning with this question: When were you born?

Margaret Nagy: I am 90 years old. I was born Jan. 10, 1924.

PR: You grew up in New York City, right?

MN: Yes, in Manhattan, downtown. Fifth St. between Aves. A and B. Later we moved to 7th St., across from Ave. A. Do you remember Tompkins Square Park?

PR: It's still there.

MN: I lived right across the street from there.

PR: Nowadays that neighborhood is called the East Village. But back then, did you call it the Lower East Side?

MN: We just called it downtown.

PR: Where were your parents from, and what did they do?

MN: My parents were both born and raised in Hungary. My father was in World War I. He was stationed in China, of all places. How he got here, I don't know. They didn't give us much information.

PR: When you say he was in World War I, do you mean he was fighting for Hungary?

MN: No no no, for the United States.

PR: So he was already in the States by then. And you were born in the States.

MN: Yes, I was born in Connecticut. Warren, Connecticut. And then my parents moved down to Manhattan before I was one year old. I have no idea why, or who brought them here, or why.

PR: What did you parents do for work?

MN: My father worked for the First National Bank on Wall Street. He was an elevator operator. You know, the ones you ran by hand.

PR: And did your mother work?

MN: Yes, after she had both of us — me and my sister — she went to work on Long Island making, of all things, corsets. Of course, she didn't talk good English.

PR: So was Hungarian spoken in your parents' home?

MN: Oh, yes. That's how I learned to speak Hungarian. My father spoke perfect English — I think he learned that in the Army — but not my mother.

PR: And you mentioned that you had a sister?

MN: Yes. She's dead now. She was exactly a year younger than me. Born on the same day, but a year later.

PR: How did you end up attending the Manhattan Trade School?

MN: My father was a funny bugger. When he learned that I liked cooking — he had a funny idea that if you liked that, and you took it up, you became a waitress. To him, there was no such thing as learning how to cook, or being trained to be a chef...

PR: You mean because you were a woman?

MN: Right. And he saw how waitresses worked. Because every day at work he ate breakfast at Schraft's, and he saw how hard they worked. So that was it — I wasn't allowed to go to any other high school.

PR: So he decided you would go to the Manhattan Trade School to learn a sewing trade?

MN: When he heard about it, yup.

PR: I keep calling it Manhattan Trade School, but it probably had a different name by the time you were there, right?

MN: Yes. It was the Manhattan School of Women's Garment Trades.

PR: Right, they changed names several times during that period. [The school was also known as Manhattan Industrial High School at one point. — PL]

PR: The school was on Lexington Avenue and 22nd St., right?

MN: Right, right.

PR: The building is still there, and it still has "Manhattan Trade School for Girls" chiseled into the façade. But it's a regular high school now.

MN: Uh-huh.

PR: Were you excited to be going there?

MN: My cousin had gone there, and she had everything good to say about it, so I figured oh well, I might as well try it. And I did.

PR: What trade did you choose to study?

MN: I had to choose millinery, because, like I said, my father wouldn't let me choose cafeteria.

PR: Oh, right, by that time they were offering cafeteria management as a trade course of study. [The school had previously offered only the needle trades (dressmaking, millinery, and etc.) and the glue trades (lampshade making, decorative box making, etc.) but began expanding its offerings around the time Margaret attended. — PL]

MN: Right. But my father wouldn't allow that. So I picked millinery. I figured I already knew how to sew.

PR: You already sewed at home?

MN: Oh yeah, I was good at it.

PR: Your mother taught you?

MN: Yeah. And my sister was good at it.

PR: And you said your mother was making corsets, so she was already in a sewing field.

MN: Right. But I wasn't crazy about it. I had to choose millinery because I didn't like garments.

PR: Oh, so you didn't want to do dressmaking or sewing machine operation.

MN: No. My sister did dressmaking, a year later.

PR: Oh, so she attended the school too?

MN: Yeah.

PR: What didn't you like about garments?

MN: I didn't like sewing. So I figured doing something hats was okay. And I learned to like it.

PR: And how long did you attend the school — one year? Two?

MN: I think three.

PR: What do you remember about your time at the school. Did you like your teachers?

MN: Oh, yeah. I remember that juniors, we had to wear smocks. A tan-colored smock that you pulled over your head. When you became a senior you were given blue smocks with buttons, and that's how everybody knew you were a senior.

PR: So these were the uniforms.

MN: Yeah. I don't think they wanted anyone to look like they could outdo someone else.

PR: And of course this was during the Depression, so that was a big concern, that everyone appeared equal and nobody looked like they were doing worse than the others.

MN: That's right.

PR: Were there other students from Hungarian families, and did you bond with them in any way?

MN: No, no. For that matter, most of the girls came, believe it or not, from Long Island and Brooklyn. Nobody came from Manhattan.

PR: So these other students, they all had much longer commutes to school than you did.

MN: Oh, yeah. They came on trains. Yup.

PR: How did you get to school?

MN: If it was a nice day, I'd walk. If not, I'd take a bus. There was a bus on Ave. A.

PR: Did you make friends with the other students?

MN: Oh, yes. That's why I don't know what became of that yearbook I had. It's in this apartment somewhere, but I can't find it.

PR: Did you stay friends with any of them later on in your life?

MN: Yes, after I graduated. There were one ... two ... three from the Bronx that I stayed friends with. And then there was one from the way, way Upper East Side, the hotsy-totsy side, where they had homes. And even after we got married, we stayed friends.

PR: What did you particularly like about the school?

MN: What I liked at the school, I loved their cafeteria.

PR [laughing]: So even if you weren't allowed to study that, you were still interested in it.

MN: Yes. When I went to eat there, I loved sweet potatoes. And when sold sweet potatoes for five cents a plate, I always saved money to buy that.

PR: The cafeteria was staffed by students, right?

MN: No, there were women there. There were women there. [The school had employed students in the cafeteria in its earlier years. — PL]

PR: By the time you attended the school, it was pretty well established and had been around for a while. But it was actually a very important school when it was founded, because it was the first girls' vocational school in America. Did they make you aware of the school's historical importance?

MN: No. Nothing about their history. Except that the war was going on.

PR: How did that affect things?

MN: Well, on Armistice Day, wherever we were — in the hall or wherever — we'd get very quiet and there'd be a bugle blowin'.

PR: You mean on the 11th hour of the 11th day, and so on, right?

MN: Right.

PR: Were there any male staffers at the school?

MN: No. Well, the young man who ran the elevator. And the janitor. But that was it.

PR: All the teachers and administrators were women?

MN: Yeah. That I remember.

PR: Did you take any class trips?

MN: Just one, for an art class. The teacher — I wish I could remember her name — I always looked forward to that. She took us out in the spring to some place, I think it was around the Central Park area. It was the first iced tea I ever had, and she showed us that if you put milk into the iced tea, she said, "Watch the milk as it goes in, and see the design and pattern it makes in the tea." She was always art-conscious.

PR: So did you do that, with the milk?

MN: Yeah!

PR: And was that eye-opening for you?

MN: Yeah. I says, "Oh, yeah, look at that!" That was different, that was something new. I mean, I lived way downtown. I didn't get any of that stuff.

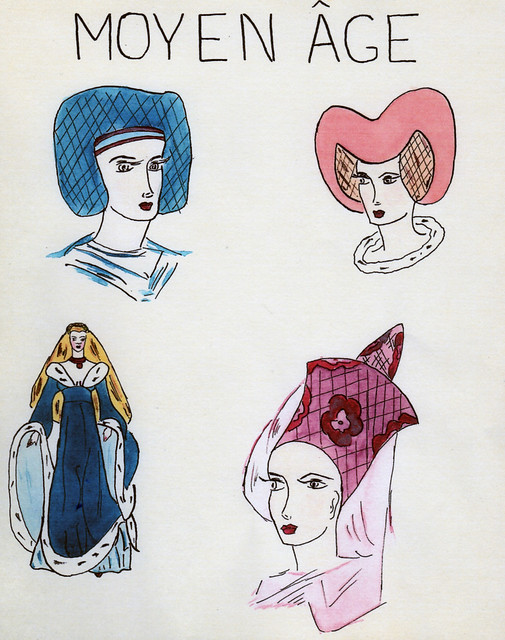

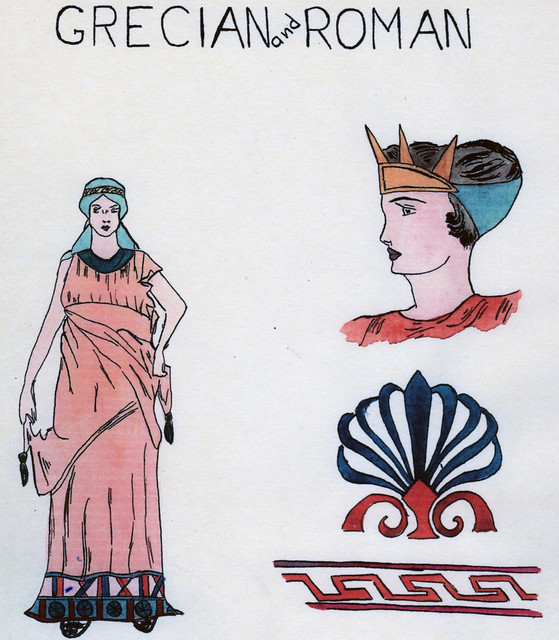

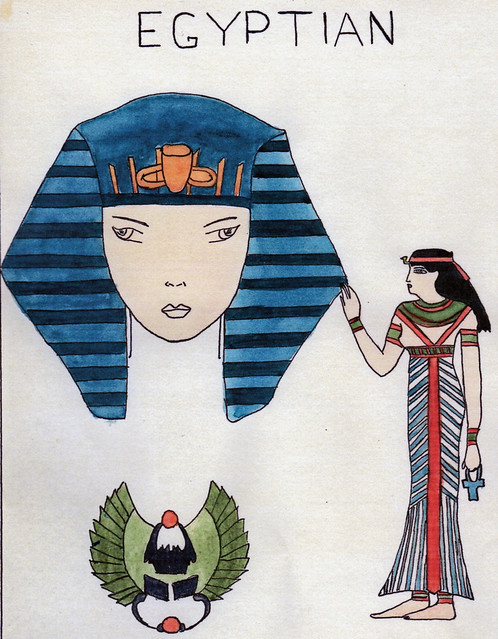

PR: Your daughter made copies of your portfolio drawings for me. What class was that for?

MN: That was art class.

PR: The same one with the teacher who showed you the milk in the iced tea?

MN: Yes, yes.

PR: Your daughter also told me that some of your drawings were displayed at the Brooklyn Museum. Can you tell me about that?

MN: I was surprised. This was part of our studies. And when we finished them, she picked some of them to go to the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Not only from us, but also from other high schools. They were displayed, to show what each school had to offer. I was really surprised, and happy.

PR: Well, sure you were — your teacher chose your work!

MN: Not only mine, there were some others, too.

PR: Right, but you were one of the ones who whose drawings were chosen.

MN: Yeah. I never saw them — I never got to go to the museum.

PR: Really? Did you mean to, and you just never got around to it?

MN: I — yeah.

PR: But hey, you've been exhibited in a fine art museum. That's more than most people can say.

MN [chuckling]: Yeah.

PR: The school had a job-placement office that arranged jobs for the students. Did they do that for you?

MN: Yes, they did.

PR: What sorts of jobs did they arrange for you?

MN: Believe it or not, nothing in millinery.

PR: Because there was nothing available..?

MN: I'm sure there was. But they gave me a job with a power sewing machine. Remember the chevrons on the [military] uniforms that the men wore? It was sewin' those things.

PR: You mean sewing sergeants' stripes and things like that onto military uniforms?

MN: Right.

PR: And that was precisely the kind of garment work you had wanted to avoid.

MN: Right! I didn't like machines. Oh, I quit that. I couldn’t do that. And it was piece work — you know what that means?

PR: You get paid by the piece, instead of by the hour.

MN: Right. How many chevrons you finished.

PR: These were Army uniforms?

MN: Yes, yes. I remember corporals' stripes, sergeants' stripes. And power machines? Why give that to me when I wasn't even used to a power machine? We didn't have that in millinery.

PR: Where was this job?

MN: Oh, it was downtown, in a crummy place, really. When I walked into the hallway, I says, "My god, what am I gettin' into?" Dark, damp. And when you went into the sewing area, a whole mess of machines, and then older women already workin' there.

PR: So you felt out of place.

MN: Yes, yes.

PR: How long did you work there before you quit?

MN: No more than two weeks.

PR: And did you go back to the school and ask for another job?

MN: No. I figure I'm out of school, that's it, I'll find one on my own.

PR: So you never made use of that office, the job placement office, again.

MN: No.

PR: What kind of job did you eventually find for yourself?

MN: I went around to different places, and believe it or not I got a job doin', again, on the sewing machine. That's what was available. But on this job I did better, so I stayed a while.

PR: And who were you working for?

MN: The Durlacher company. Durlacher — D-U-R-L-A-C-H-E-R. It was the man who, I guess, owned the place, it was his name. And it was half and half: Half was sewing machines, and the other half was shipping, packing, and stuff like that.

PR: And what did you sew there?

MN: Remember the bandoliers that the soldiers would wear? They were canvas, and they'd put bullets in them. We'd make those. And then we stopped makin' those, when I guess they ran out of their contract. And then they put me on the other side, with the shipping and everything, and I worked on packaging monograms. No more machines.

But then! The airplane scarves — remember how the pilots wore these long white scarves?

PR: Yes.

MN: Okay. They gave me the job of stamping "U.S. Navy" or "U.S. Army" or "USA" onto the scarves.

PR: Stamping with what?

MN: Just a regular ink pad. But it had to be just right, just so. That was another contract, but then that fizzled out too. And before you know it, my husband was coming home from overseas.

PR: Wait, when had you gotten married in the middle of all this?

MN: I didn't. I waited for him to come home.

PR: Oh. So how did you meet him?

MN: Oh, my lord, I met him at a sweet 16 party.

PR: Your sweet 16 party?

MN: No. My cousin's, in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

PR: How old were you at the time?

MN: Oh god — not 16 yet.

PR: And how old was he?

MN: About 17, 18.

PR: Oh, a much older man!

MN: I know.

PR: Did he live in New York, like you did?

MN: No. He lived in New Brunswick.

PR: So the two of you courted while you were living in different states?

MN: Yes. He'd come in on weekends. Then he was drafted, went into the Army, stayed in England about three years. And then when he came home, he couldn't wait — within 15 days, we were married.

PR: So he wrote to you while he was away?

MN: Yes, I have all of them saved. But he was not allowed to send a letter he wrote. They took the letters and scratched out the parts they didn't want in there.

PR: Once you got married, did you keep working?

MN: Yeah, I started working pretty soon after we got married. I worked for Maidenform, which was in New Jersey.

PR: So after you got married, the two of you moved to New Jersey?

MN: Oh, yes, and was I glad. I hated New York.

PR: Really?

MN: Oh, yeah. I still do!

PR: And what happened to your job at Durlacher?

MN: I got a phone call, on Durlacher's phone, from my husband. He'd just got off the boat! He didn't even go home first — he got to a phone and called the number. And I looked at Mr. Durlacher — he was standin' there, along with Mr. Smith, another one — and I says, "That was my boyfriend from overseas. His boat just got in." And to this day, I'm sorry I said this. I says, "To hell with this job. I'm goin' home, I'm gettin' married."

PR: Oh, wow.

MN: Which I did. I never saw them again.

PR: How long had you been working there at that point?

MN: Mmmm, I'd say a good two years.

PR: Why do you regret having said that?

MN: It was a nice place to work, and I didn't want to say that type of thing — "To hell with the job."

PR: So even if you were going to leave, you didn't have to leave that way.

MN: That's right. But I don't think they cared, really.

PR: So then you moved to New Jersey with your husband. What was his name?

MN: Frank Nagy.

PR: And then you got the job with Maidenform?

MN: Yes.

PR: What did you do for them?

MN: Would you believe machine work again? Oh, yeah. But on this one I was better. And I got pregnant, and then I left.

PR: Maidenform is a brassiere company. Is that what you were making?

MN: Yeah.

PR: That's pretty funny — your mom made corsets and you made brassieres!

MN: Right, right.

PR: What about Frank, what did he do?

MN: He worked for the Army at the Raritan Arsenal, in Raritan, New Jersey, before he was drafted. They had a condition there — if he was inducted, his job would be waiting for him when he was discharged. And that's just what happened. He went back to work there.

PR: What did he do there?

MN: Oh, brother. Before he left, he worked with explosives. But after he came home he was a heavy equipment operator. Big trucks and all that. And then he retired from there. It was the only job he ever had.

PR: Did you ever go back to work?

MN: Yes — at another sewing machine job.

PR: Sewing what?

MN: Making pajamas. I was good at it. I don't remember the name of the company. I enjoyed it because I was good at it. I did that as a night job for about a year.

PR: When did you stop working?

MN: By the time I was in my 30s, because I had three girls by then.

PR: Even when you weren't working, did you continue to sew, like at home?

MN [laughing]: No! I mean, I'd sew buttons or stuff like that, but that's all. I did not enjoy it.

PR: And did you ever get to use your millinery training?

MN: No, not for work. I did stuff like that at home, for my own pleasure — I made hats and turbans. But never for work. And that was a shame. I knew enough. They could have stuck me in.

PR: Do you have anything you want to add about the school, or about anything else?

MN: Well, it was a nice school to go to. And there was a little old lady there who taught you how to iron. And the iron was a flatiron that you put on a coal stove — not electric. And naturally, cafeteria, I enjoyed that.

And my millinery teacher, when we started, she was a maiden. And then she got married, so she had two names. And then there was another millinery teacher, and whoa, she was a whoop-de-do.

PR [laughing]: A whoop-de-do? What does that mean?

MN: The clothes that that woman wore, and the earrings! She had heavy earrings. She was some dresser, with some hairdo. The art teacher, she was lovely. I remember the arithmetic teacher — she lived on Ave. A, of all places.

PR: Oh, right near you!

MN: Yeah, but not the same — how should I say it? Not the same people. It was a big difference. I lived across the street from a doctor, but you would never have known it by looking at the place where I lived.

PR: Tell me about your place.

MN: It was a tenement. A kitchen, a dining room, and two bedrooms, without windows. In the summer, you nearly died. Across the street, the doctor's building — what a difference. And there was a dentist across the street. You would never know that I lived in that area.

PR: How long did your parents live there?

MN: Until we moved to 7th St., when I was about 17. Whaaat a difference. We had a dentist's office on the main floor, and we had a dining room, a parlor, a big bedroom, and two other bedrooms. So there was a biiiig difference. On 5th St., the first place, it was, to me, a slum. It was not what we liked.

PR: What about your sister — did she stay in New York?

MN: She lived in New York until she bought a home out in Jersey.

PR: Did she end up using her trade skills that she learned at the school?

MN: Ooooh, yes, I give her that much. She knew how to make patterns, how to design clothes, how to sew clothes, and she had a little business of her own.

PR: A sewing business?

MN: Yes. And she worked for a designer, a clothing designer. She used what she learned there.

PR: So it sounds like you didn't get to use your millinery skills because they didn't send you to the right jobs. But I guess they sent her to the right jobs.

MN: Yes, they did. They did. I can't think of the designer's name who she worked for — Rosen-something.

PR: Oh! You mean Nettie Rosenstein?

MN: That sounds familiar, yes. A famous dress designer.

PR: Wow. It turns out that another student from the school, whose report card I happen to have, ended up working for her and became her sister-in-law. I wrote a story about her a few years ago. That's pretty amazing, that another student from the school went to work for her.

MN: It's too bad my sister is dead. She could have told you lots more about it.

———————

At this point I sensed that Margaret's energy was fading a bit, so I thanked her for her time and her recollections and wrapped things up. She said, "I don't know what you possibly got out of this," but I assured her that I'd gotten plenty from our discussion.

As I look over the transcript of our chat, I now find myself thinking of dozens of additional questions I wish I'd asked her, especially regarding her portfolio drawings. Hmmmm — maybe I'll try to arrange a follow-up call.

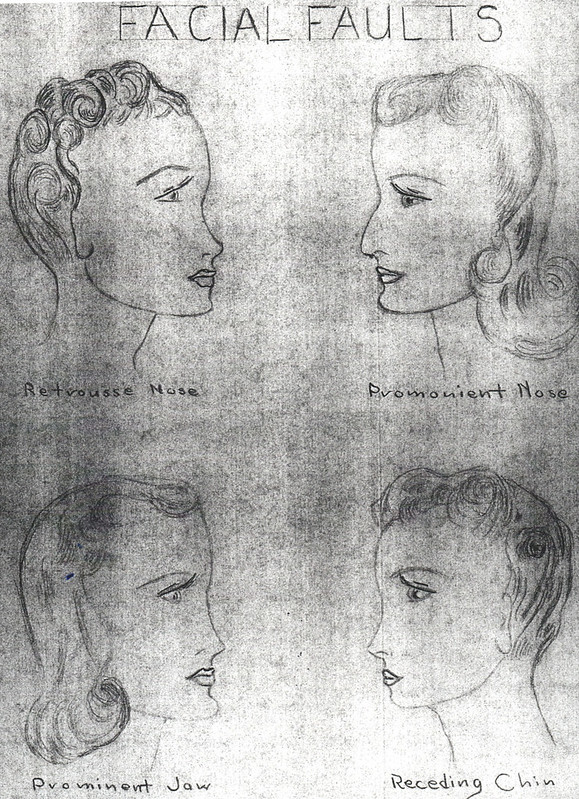

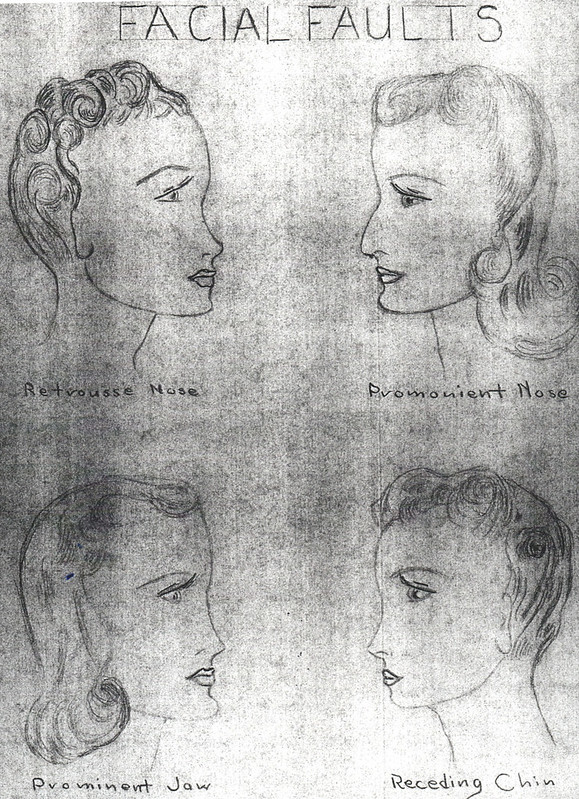

I want to conclude with one more sampling from Margaret's portfolio. I left it for the end because the quality of the image is poor, but in some ways it's my favorite page of the bunch. Apparently millinery students had to be aware of people's "facial faults":

(Extra-special thanks to Margaret Nagy for sharing her story with me, and to her daughter, Carol Chadwick, for making all of this possible.)