Today we're going take a look at Augustina Garcia, a dressmaking student who attended the Manhattan Trade School for Girls — or, as it was known at the time, Manhattan Industrial High School — in the mid- to late 1930s.

Augustina's case is particularly interesting because she's one of the very few Hispanic students in my report card collection. On her primary card, shown above, her nationality is listed as "Porto Rican" — an embarrassing misspelling on the part of the school's staff, whose spelling and grammar were usually impeccable. (For more on this, scroll down to the update at the bottom of this entry.)

Next to "Porto Rican" is a partial black dot. As I've explained in previous entries, the black dot was routinely included for black students. It's not clear whether Augustina's partial dot was intentional (a full dot for blacks, a partial dot for Hispanics?) or if the dot sticker simply tore.

What else can we learn from this card? There was some dispute over Augustina's date of birth; neither of her parents worked (keep in mind that this was during the depths of the Great Depression); she was deemed to be 18 pounds underweight; and she took cod liver oil three times a day to combat colds and sore throats.

Now let's take a look at Augustina's grades and teacher comments (as always, E = Excellent; G = Good; F = Fair; P = Poor):

Several themes emerge here. First, Augustina's grades were a bit below average. Second, several teachers noted that she was a slow worker. And third, it was repeatedly noted that she was left-handed, which was presumably an impediment (or at least something that had to be accounted for) when working on a sewing machine or following a pattern. This was during the period when lefties were often forced by schools to retrain themselves to be righties, but there's no indication that this was done to Augustina. (As an aside, I'm left-handed myself, so I'm particularly interested in this storyline.)

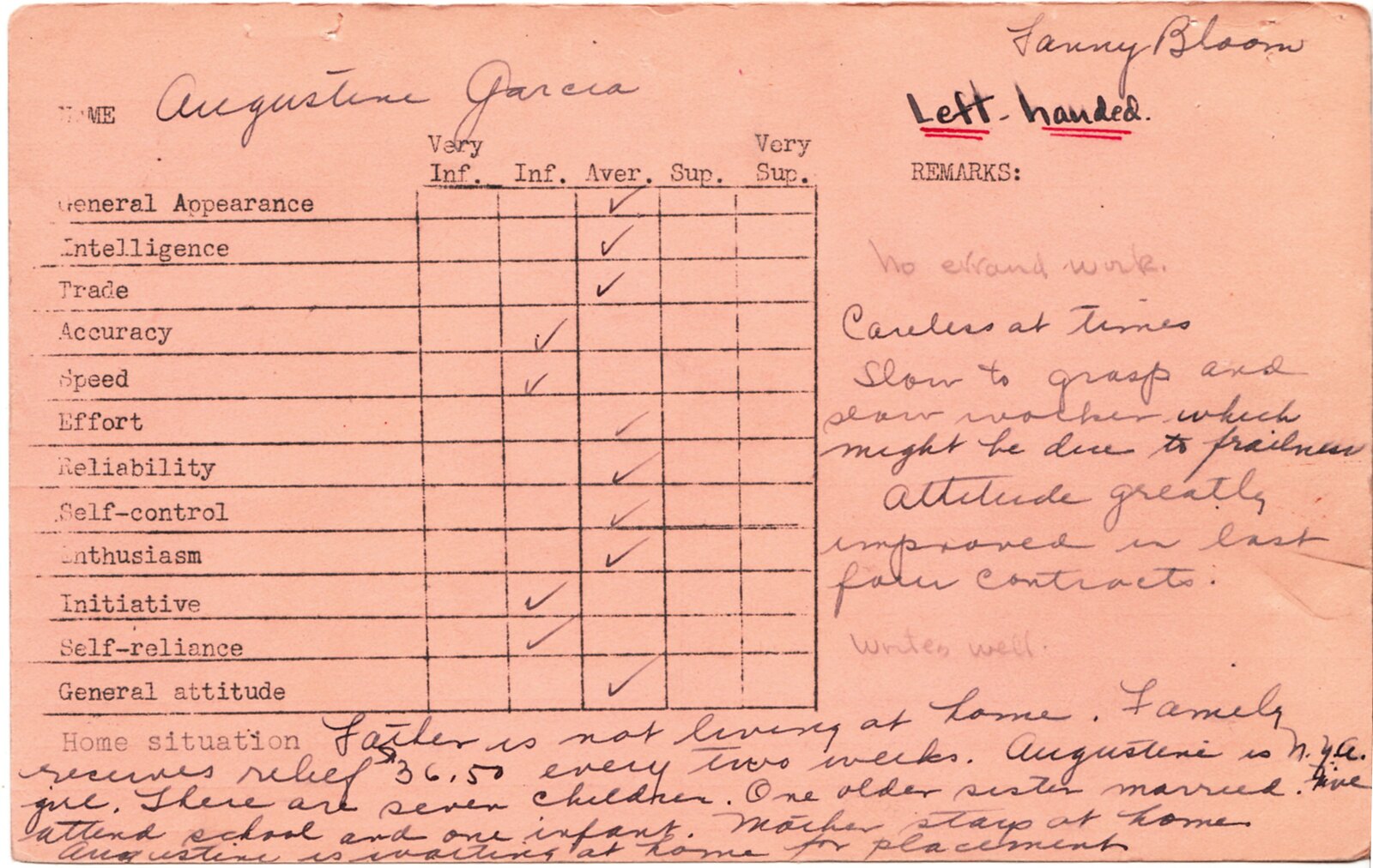

Augustina's handedness and her slightly below-average ranking are both referenced again on this next card, which was prepared by the school's job placement office in anticipation of finding work for her after she finished her vocational classes:

Here's a transcription of the handwritten notes:

Careless at times. Slow to grasp and slow worker, which might be due to frailness.Attitude greatly improved in last fall contracts.

Writes well.

Father is not living at home. Family receives relief [of] $36.50 every two weeks. Augustina is NYA girl. There are seven children. One older sister [is] married. Five attend school and one infant. Mother stays at home. Augustina is waiting at home for placement.

Augustina was eventually sent out to three jobs:

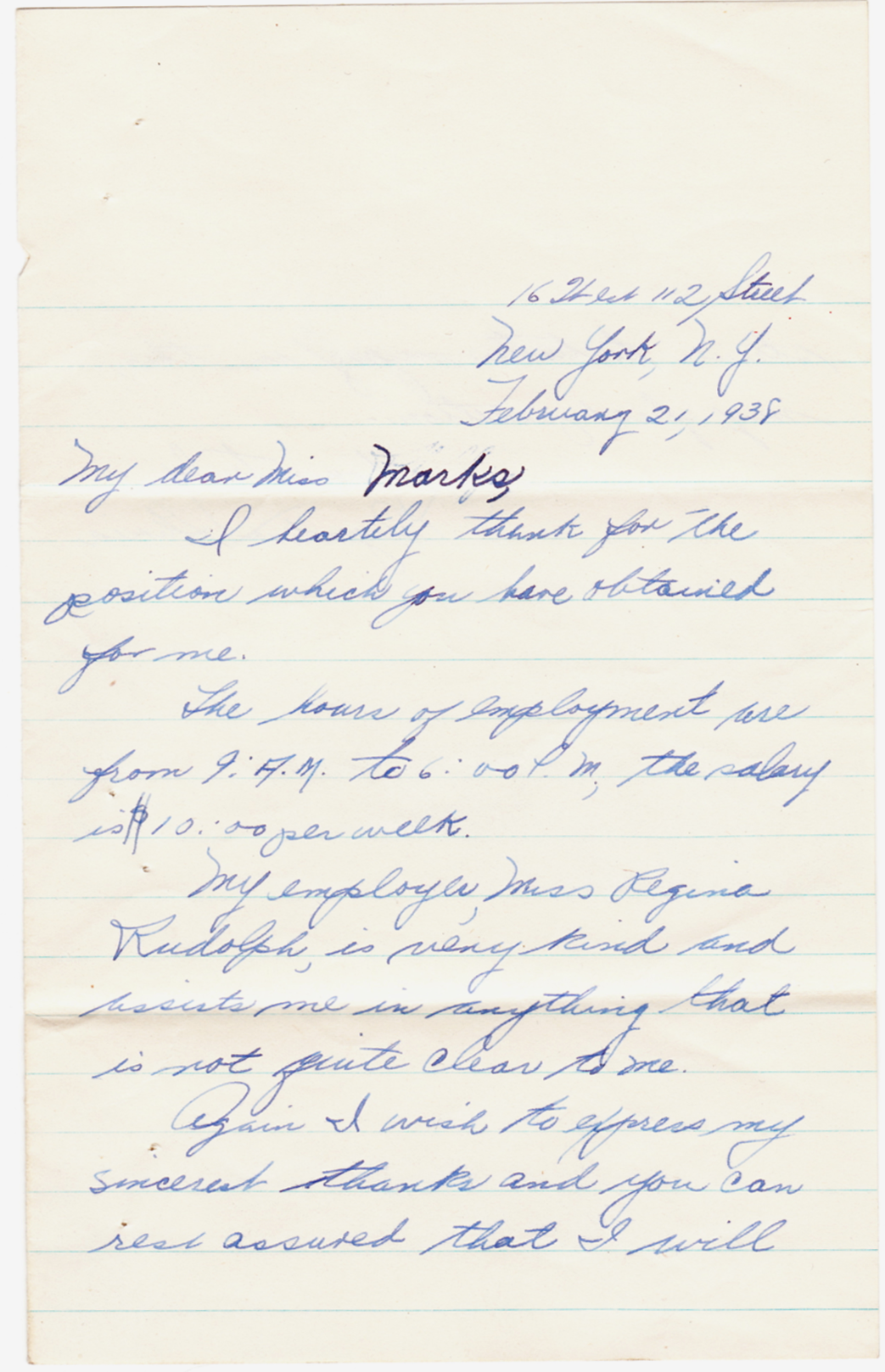

The first job, a five-day stint working for an employer named Regina Rudolph, entailed "errands, to clean, etc." On Feb. 21, 1938 — the fourth of the five days — everything seemed to be going well, as spelled out in this note that Augustina sent to the school:

The letter reads like so:

My Dear Miss Marks,I heartily thank [you] for the position which you have obtained for me.

The hours of employment are from 9am to 6pm; the salary is $10 per week.

My employer, Miss Regina Rudolph, is very kind and assists me in anything that is not quite clear to me.

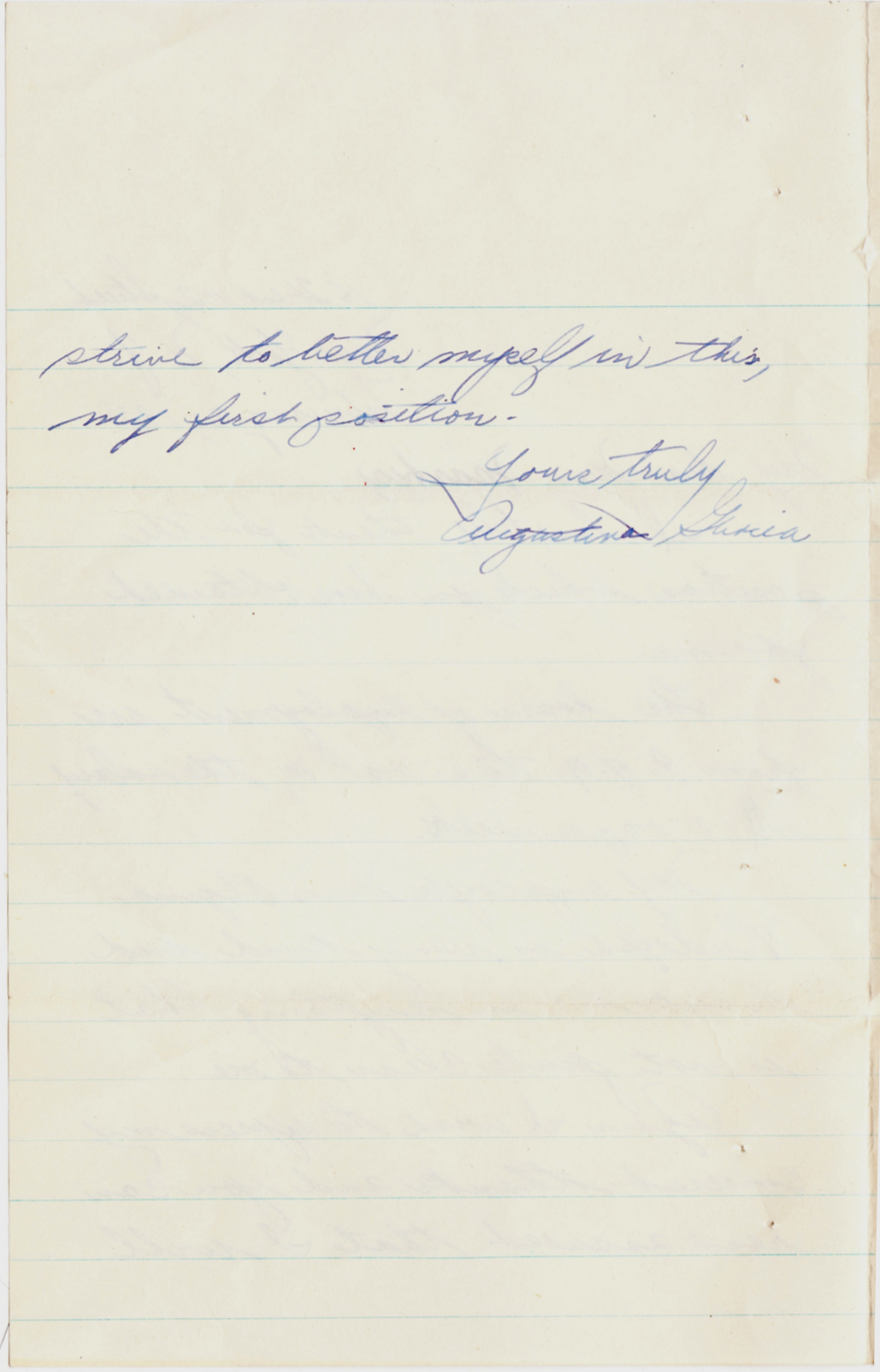

Again I wish to express my sincerest thanks and you can rest assured that I will strive to better myself in this, my first position.

Yours truly,

Augustina Garcia

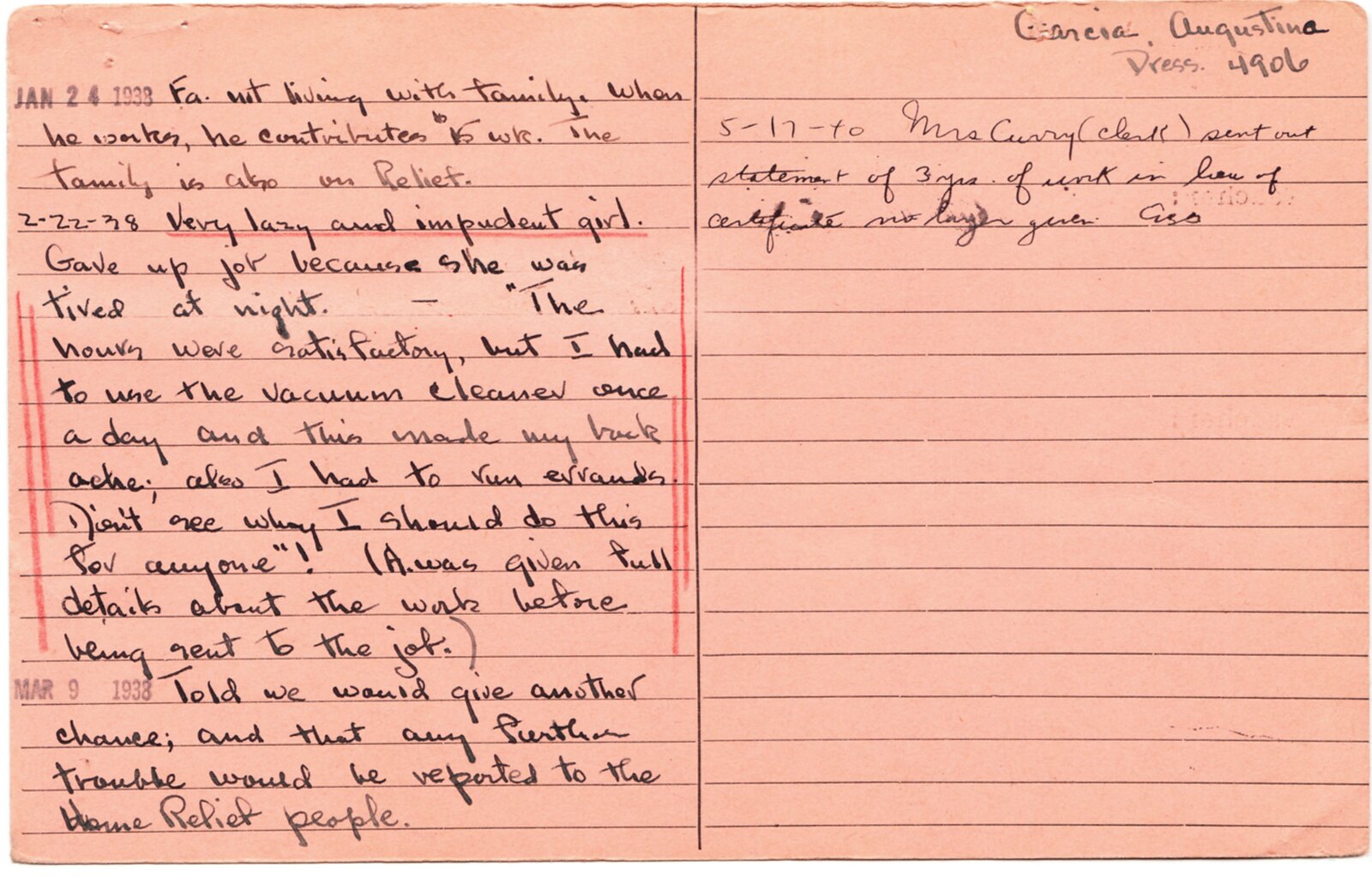

But something must have gone wrong along the way. The day after this letter was written, Augustina left the position. If you scroll back up to the yellow card, you can see that she left because "Work too hard! See note." The note being referred to there can be found on this next card, outlined in red:

The note, which is unsigned but is rendered in the telltale handwriting of the school's very demanding job placement secretary, Althea Kotter, reads as follows:

Feb. 22, 1938: Very lazy and impudent girl Gave up job because she was tired at night. "The hours were satisfactory, but I had to use the vacuum cleaner once a day and this made my back ache; also I to to run errands. Don't see why I should do this for anyone"! (Augustina was given full details about the work before being sent to the job.)March 9, 1938: Told we would give another chance, and that any further trouble would be reported to the Home Relief people.

Yowza. Whatever the specifics of the dispute, it does seem odd that Augustina was sent to vacuum and run errands after having been trained in dressmaking, and one wonders if her ethnicity had anything to do with it. If you scroll back up to the yellow card, you can see that her next two jobs involved hand sewing — in one case at a home for the aged and then for a lampshade manufacturer — but at no point did the school send her out for dressmaking work. Hmmmm.

If anyone knows more about Augustina, please get in touch. Thanks.

Update: Reader Miriam Sicherman informs me that "Porto Rico" was actually an accepted spelling in the early 1900s. That's confirmed by this Wikipedia entry, which includes the following:

In 1932, the U.S. Congress officially corrected what it had been misspelling as Porto Rico back into Puerto Rico. It had been using the former spelling in its legislative and judicial records since it acquired the territory. Patricia Gherovici states that both "Porto Rico" and "Puerto Rico" were used interchangeably in the news media and documentation before, during, and after the U.S. invasion of the island in 1898. The "Porto" spelling, for instance, was used in the Treaty of Paris, but "Puerto" was used by The New York Times that same year. Nancy Morris clarifies that "a curious oversight in the drafting of the Foraker Act caused the name of the island to be officially misspelled."

Augustina enrolled at Manhattan Trade in 1935, so the official spelling had been established as "Puerto" for three years by then. Still, in light of this new information (or at least it's new to me), the "Porto" designation on Augustina's card no longer looks quite so egregious.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteIf it was during the Great Depression I suppose that it wouldn't be unheard of for them not to be able to find a position in the field that the student studied. I know many people who do that today. I wonder if the positions after the first one went better for her.

ReplyDeleteI find it difficult to control my reaction to the words that were written. I don't have experience reading items like this from that area and/or from that era. I would suspect that it wouldn't stand out from other documents of the same area and era. That's not to say that I am justifying anything, but I suppose if one is studying history one has to maintain perspective.