Click to enlarge

Permanent Record is all about uncovering the stories lurking within found objects. It's a determinedly fact-based approach, employing archival research to determine what really happened.

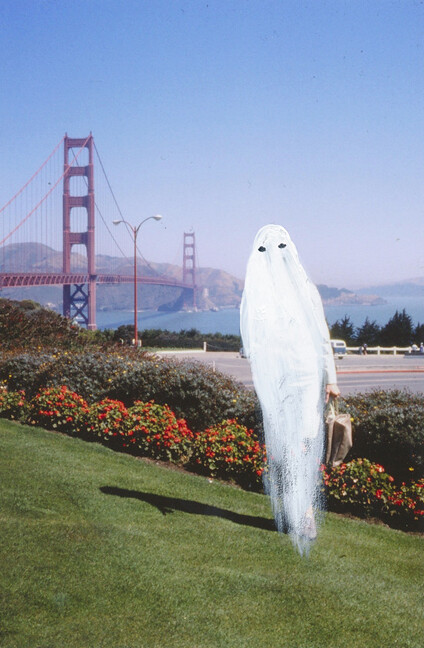

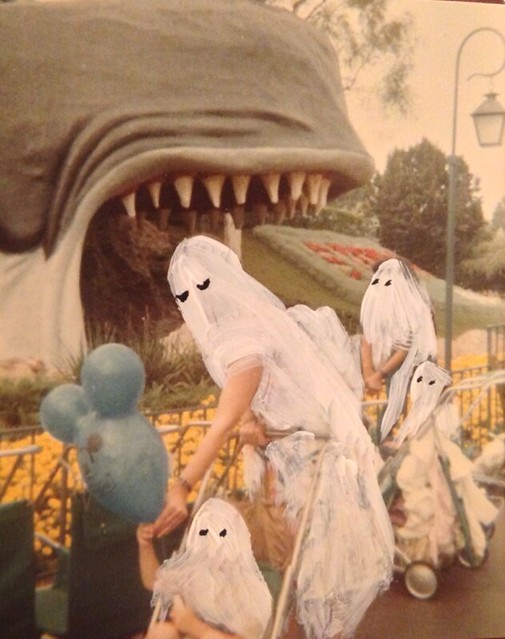

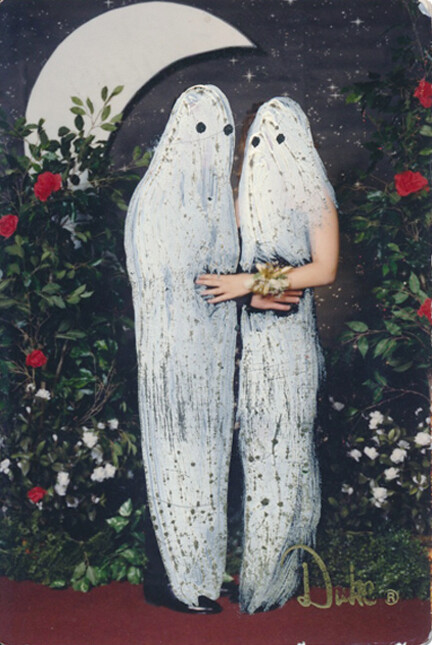

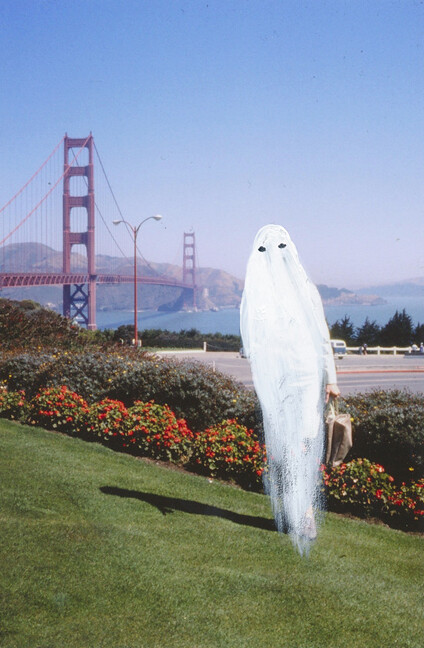

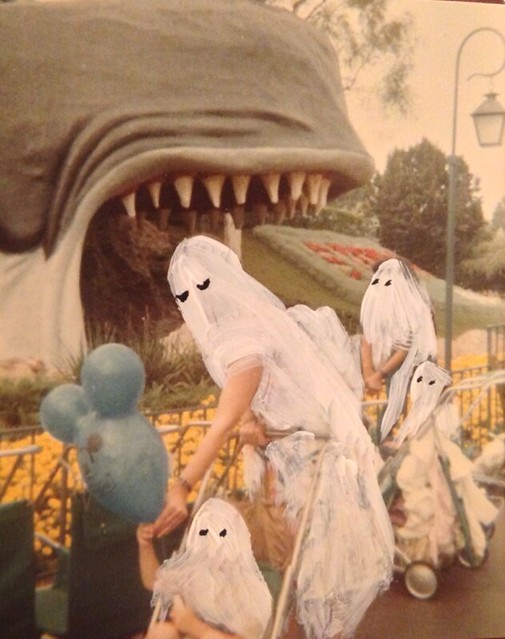

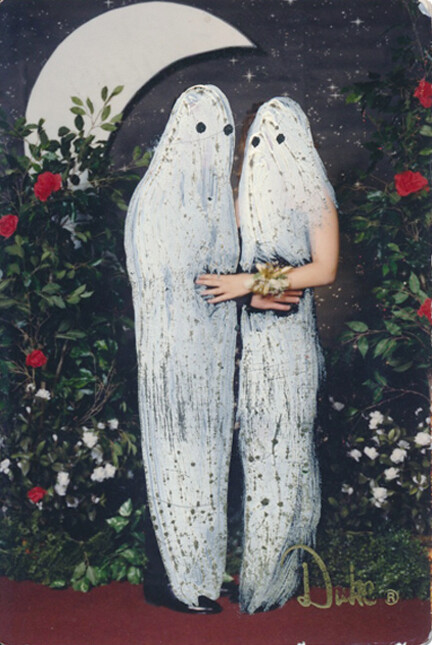

But found objects also provide lots of opportunities to spin fantasies about what might have been, or to project ourselves into other people's stories, or just to mess around with our perceptions of reality. That's the approach taken by the Florida-based artist Angela Deane, who has a very interesting specialty: She procures old snapshots and paints over most of the people in those photos, transforming them into ghosts. The resulting images, which she calls ghost photographs, can be seen on her Tumblr site (from which all the images in this PermaRec entry were taken).

Deane's response to found objects is obviously very different from mine, which is precisely why I find her project so interesting. It would never even occur to me to modify or alter an artifact like she does. But hey, that's why she's an artist and I'm a journalist, right?

In any case, Deane and I both find inspiration in found objects, so I wanted to learn more about her project. She recently agreed to answer a bunch of my questions via email:

Permanent Record: When and how did you decide to start this project? What was the impetus?

Angela Deane: I started it by a happy accident, really. In the fall of 2012 I had an artist residency in New Mexico. I had bought a bunch of photographs on eBay and at thrift stores, which I planned to use to create collages. When I spread out the photos in my studio, I started wondering what would it be like/mean/look like to paint a ghost over a photograph, to erase the particular of an identity or the ownership of an experience. And so I launched in.

Hours later I sat back and stared down at about 40 or so "ghosted" pictures and was blown away. I knew I was on to something.

PR: Roughly how many ghost photos have you made? Have you posted all of them on your Tumblr site? If not, how many more have you done besides the ones on the site, and how do you decide which ones go on the site and which ones don't?

AD: I'm on about number 325. Only a handful are on the Tumblr site. Being fairly new to it, I'm taking my time and picking and choosing mostly on whim. Recently I've been sourcing photos based on themes (embraces, birthday parties, parades), so they may post in waves of these moods for some time to come.

PR: Where do you get the found photos? Like, do you hunt for them at flea markets? Did you already have a big stash of them when you started this project?

AD: My initial stash was probably about 100, sourced mostly from eBay and from some from thrift stores in Miami and other places in Florida. In New Mexico I met this guy who had a whole garage full of photos — he even had a deal with all the local thrift stores to give him any of the photos they received first — so I struck a deal with him and got to go through a lot of boxes out there. Got some great ones. I'm back south for the spring and summer, so I'll definitely be hitting up some flea markets! I'll be looking for some good vacation photos, I think.

PR: How do you decide if a photo is "good enough" or "right" for being painted? Is there a particular type of scene (or feel, or whatever) that you look for?

AD: Mmmm, it remains much of a mystery why I choose the ones I do. In general I'd say I look more for color photos (black and whites make it a little more morbid; more about death, which isn't really how I think of them). I like snapshots. In essence they're just these little moments, generally when people are feeling good, are engaged with one another or with nature. I like those moments where you can feel a pulse in the inattention of what's taking place. Does that make sense?

PR: Why ghosts?

AD: There's a line from a Band of Horses song that goes,

"We are the ever-living ghost of what once was." I think of these ghosts not as of people that have passed but each and every one of own experiences that has passed. How to hold memories has always been something that has provoked me to create lots of my art in life. Can we retain them as experiences or do they just turn into anecdotes?

These are intended as ghosts of moments. And in painting away the specificity of the people experiencing them, I like to think it opens things up for any of us to place or project ourselves into that space. They could be our memories now. Of course, that is what a life ends up to be — a collection of moments, experiences, memory — so ultimately I suppose it does grapple with mortality. But I don't think of them morbidly.

And I notice that the ghost photos make most people smile or laugh, which is great. I think the choice of the snapshots contributes to this. A writer on Flavorwire the other day described them as "ghosts having fun" and then did a riff on the whole celebrity mag thing and said, "Ghosts: They're just like us!" I loved it.

PR: What paint (or white-out, or whatever) do you use to paint the ghosts?

AD: Mostly acrylic, sometimes gouache.

PR: How long does one of the photo paintings typically take you?

AD: Most of them take only about 30 minutes or so, but lately I've been doing some with upwards of 100 or 200 ghosts in them, and I spend a few hours with those.

PR: At first I thought you turned every person in each photo into a ghost. But then I saw you sometimes leave some people un-ghosted (like the people in the background of this shot). Is there a rule or system you use when deciding who gets ghosted and who doesn't?

AD: Not really; just a gut feeling. Sometimes I imagine myself as the un-ghosted people, looking on at the "ghosts" and "spaces to project other people in" and want to keep them intact so they can be more concrete witnesses to something magical happening. It gives a different focus to the ghosted characters. And once in awhile it's just as simple as finding their face simpatico, or liking their stance, and therefore wanting to leave them intact.

PR: Do people send found photos to you to paint, either for commissions or just as a "I thought you'd like to have this" kind of thing?

AD: Yeah, I have a few commissions under my belt. I love doing them. This past December I had a show with F.L.A. Gallery and was put in touch with Amy Sedaris, who is crazy for ghosts and commissioned me to paint a bunch of family photos to gift to her siblings. Very cool!

PR: Have you had any other ghost photo gallery shows besides that one?

AD: Yeah, I've had a couple. The last was in Los Angeles at a friend's spot called "Matters of Space" in Highland Park. It was well-received and has brought me a couple projects in the works, which I can't get into yet but are very exciting. The F.L.A. Gallery show was also terrific and was so beneficial, as it was the first time I'd seen so many of the photos framed in a group rather than just in my studio.

PR: Have you ever tried to find any of the people in any of these photos, and/or has anyone ever told you, "Hey, I recognize that photo"?

AD: Only once, out in New Mexico! And actually I never painted over that photo because it's so great — an older man out in his front lawn, standing proud. Sometimes there are names written on the back of the photos, but I've never thought to Google anyone. Maybe I should..? Hope they'd be cool with being turned into spirits.

I also haven't done any personal photos of my own yet. But may do a few soon. Some goofy ones from junior high or something, maybe my softball team portrait.

PR: How long do you think this project will keep going?

AD: I keep getting nervous that I'm not "over" it yet. But I gotta tell you, my curiosity remains piqued with each one that I make. And they're just beginning to get out into the world to such a nice reception, which makes me feel okay for wanting to paint maybe 3,000 of these guys. These last few years I've been bouncing around cities (Miami, New York, Seattle, Gainesville), so the fact that these are so portable — very different from my larger-scale paintings — is pretty addictive.

PR: Any other thoughts about found objects?

AD: Just that I love them. Much of my décor is second-hand. I love the hunt of it, I love the slow meandering and contemplation of the hunt — it's never speedy. Stories that are embedded yet unknown, endless mystery in objects and a reminder that time just continues on.

My thanks to Angela for answering all my questions. I was particularly struck by this passage from one of her responses: "How to hold memories has always been something that has provoked me to create lots of my art in life. Can we retain them as experiences or do they just turn into anecdotes?"

I totally relate to this notion of experience morphing into anecdotes. You start by experiencing something, and then proceed to remembering that experience. But if it's a memory that you tell or explain to others, sometimes the memory gets superceded by the telling and retelling of the memory, until you no longer remember the original experience — you just remember how you've told the story, like a script that you've internalized. Or at least that's what I've often found to be the case. Even the experience that gave birth to the Permanent Record project — the night I found the old Manhattan Trade School report cards at my friend Gina's birthday party in 1996 — falls into this category. I don't really remember much about that night anymore; what I remember is the countless times I've told the story about that night. That troubles me a bit, because it feels like the original experience has gotten lost along the way.

For those who want to see and hear more about Angela's work, here's a good video interview with her, which was produced in conjunction with one of her recent gallery shows:

(Extra-special thanks to Heather McCabe for bringing Angela's Tumblr site to my attention.)