.

In 1998, a 20-something guy named Jesse Reklaw was doing some Dumpster diving on the campus of an Ivy League university that he'd rather not name when he came across a bunch discarded of Ph.D. applicant files from the mid-1960s through the mid-1970s. Each file included a photo of the applicant, along with assorted paperwork, including feedback from university officials.

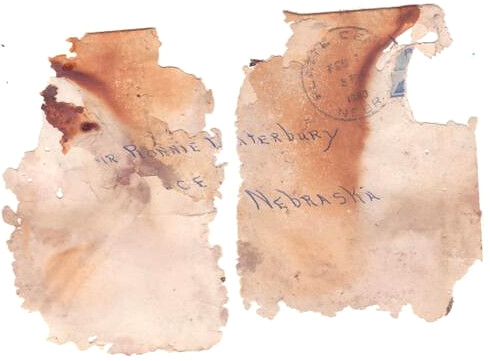

Reklaw was smitten with the photos and decided to create a zine that would show several dozen of them, each accompanied by a line of commentary taken from the applicant's file — sometimes a few sentences, sometimes as little as one or two words. You can see some examples above.

Reklaw called the resulting zine Applicant. There was only one issue, which he distributed from 1998 though 2005. The small press Microcosm then picked it up and published Applicant as a tiny book, which remains in print today.

I learned about Applicant only a few weeks ago. I'm not sure what took me so long — I love projects involving found objects, and I was very active in the zine world in the late ’90s, when Reklaw published Applicant. I'm surprised it never came across my radar until now.

Better late than never. Once I saw Applicant, I was struck by its similarities to the original Permanent Record project with the old report cards, and I loved Reklaw's simple photo/caption pairings. Individually, many of them are quite affecting; cumulatively, they tell a series of stories. It's a great project. But it also left me with a lot of questions.

Reklaw is now an artist (you can learn more about him here). Last week I contacted him and asked if he'd be willing to do a phone interview. He readily agreed. Here's how it went:

Permanent Record: How did you come across the Ph.D. applicant files?

Jesse Reklaw: It was 1998, I had just dropped out of grad school myself, and I was feeling very bitter. I didn't really have a job, and I was keeping these weird hours. I would go over to the compost and recycling bins at the school I'd been attending and dig through those to find magazines that I'd tear up and make collages out of and crazy shit like that. And I just found them all right there in the recycling bin.

PR: How many individual files were there?

JR: It was stack three to four feet high. There were well over 100 files — maybe 120. Some of the files were huge, others were incomplete.

PR: What was your original thought in terms of what you'd do with them, and how did you eventually arrive at the decision to publish them?

JR: I am mostly a 2-D artist, and I had gotten a degree in painting. I'd been doing a lot of collage work, and I was really inspired by that notion of grabbing ephemera and sticking it down on a page and then photocopying it, so maybe that's where the impulse came from. It seemed very zine-y — that whole notion of found ephemera and bringing that to light.

PR: After you acquired the files, how long did it take you to decide on the zine approach?

JR: About two weeks. I immediately started reading through them, and as I did that I saw that there was too much information to put in one giant picture or collage, so the zine format made more sense. I'd never made a zine before. Well, I'd made comics zines, but never a zine that wasn't comics-based.

PR: In Applicant, you just show the head shots and a snippet of commentary for each one. Have you ever published any of the other paperwork from the files?

JR: No. I didn't want to get sued, for one thing. I wanted to make the zine to be like a story — I'd been trained in narrative. And by juxtaposing the images and the commentary, I was able to create that. A lot of the additional commentary became very repetitive.

PR: So what did you do with all the other paperwork? Do you still have it?

JR: No. For the first 100 or 200 copies of the zine, I stapled in pages from the original application files.

PR: You mean you threw in an additional page or two as a sort of "bonus treat" in each copy of the zine?

JR: I stapled them in as endpapers. I rotated them about 30 degrees, trimmed them, and stapled them in as endpapers.

PR: How many copies of the zine did you distribute?

JR: I made about 200 with the endpapers made from the original application sheets, and then about 800 more that had facsimile endpapers, because I had run out of the original paperwork from the files. So figure about 1,000 copies over the course of seven years, and most of those were distributed by Microcosm [the same company that published the version of Applicant that's currently in print]. It was getting to be such a pain to assemble the zine and hand if off to Microcosm, and they're such a wonderful company, so I just trusted them to publish it.

PR: And how many copies of the Microcosm edition have there been?

JR: They're on their third printing of 3,000 copies.

PR: Is the Microcosm edition more or less identical to the zine version? Like, in terms of trim size, content, and so on?

JR: Yeah. The cover is a little different, and I insisted on the Microcosm version having a real spine [i.e., with the title, author, and publisher all listed], which the hand-made zine didn't have. And it doesn't have the endpapers. But otherwise it's the same.

PR: With 10,000 copies in circulation, have you ever heard from any of the people whose faces are shown in Applicant, or maybe from someone who recognized one of them?

JR: Yeah, the latter. One woman, who went to the school where I found the files and is now a neuroscientist, one of her professors from when she got her degree is shown in the book.

PR: So did she contact you and say, "Hey, I know this guy!" or what?

JR: You know, it's funny, I knew her through a different project where I draw people's dreams as comic strips, and she was one of the people whose dreams I drew, and then she got a copy of Applicant and recognized the guy.

PR: Wow, that's an amazing coincidence! Did either she or you notify the guy?

JR: No way. No way.

PR: So you asked her not to.

JR: Yeah.

PR: Why?

JR: I just don't want to get sued. There are a lot of famous cases, like when Andy Warhol took what he thought were these random photos of Italian men and put them up in a gallery with adjectives underneath them. But they were real people — you can't just use someone's likeness without asking them.

PR: It's interesting that the files included photos in the first place.

JR: Yeah, that was required back then, just to show them that you could comb your hair or something. And then some of the comments in the files refer to their physical appearance.

PR: Yeah, it seems like it would be better if it were a blind process.

JR: Which is how it is now.

PR: You don't list the names of the people whose head shots are shown, but I assume you know their names, or at least you did at one time. When you found the files, Google and other online search tools didn't yet exist, but now it would be fairly easy for you to find what had happened to these people. Have you done that?

JR: I haven't done that either. Part of it, again, is the legal risk. I might be tempted to contact one of them, and that would be stalking.

PR: Really? One could call it just research, or even curiosity.

JR [laughing]: Yeah, "research." That's what I'm gonna tell the police the next time I'm camped out outside somebody's window.

PR: Well, that would be stalking, but it's not illegal to Google someone's name. But if you don't want to go there, for whatever reason, of course that's totally fine.

JR: Yeah, it just seemed like that wasn't part of the art project.

PR: Have you ever created an online version of Applicant?

JR: No, but I've had plenty of people offer.

PR: Why haven't you done it?

JR: At this point I feel like this project has fulfilled my artistic interests. Also, from a design standpoint, I think it works better as a book than as a website. And if I put it online, I think people will stop getting the book.

PR: Have you ever done anything else with the files or the photos aside from publishing them? Like, have you ever done a gallery exhibit or something like that?

JR: No. I sort of had a manic phase last summer where I was getting rid of all my things, so I was selling them at the Portland Zine Symposium for 10¢ each.

PR: Oh wow, that was my next question, whether you still had the original files.

JR: Well, the application paperwork from the files was recycled into the endpapers. All I had saved were the photos. That's what I was selling for 10¢. I still have some that I saved for myself. I can send you one or two if you want.

PR: No, you don't have to do that. So you had removed the photos from the files, because they had been stapled in or something like that, right?

JR: Yeah. Right from the start, I loved the photos. That's what I was always more interested in.

PR: What size are they? Like, are they little passport-size photos?

JR: Yes, totally. And they're all black-and-white.

PR: In your preface, and also in our discussion here, you've addressed the question of whether it's ethical or even legal to publish this content. How hard did you wrestle with that, and can you describe your thought process?

JR: It did concern me, and I asked a lot of family members and friends, most of whom advised me not to do it.

PR: From a legal standpoint or an ethical standpoint?

JR: Legal. No one cared about the ethics. No way. I was more concerned about the ethics. Like, is it fair to run this guy's photo and say he's best defined by the words "Rather tense"? That's a call I had to make.

PR: Yeah, it's hard to distill something down to a single sentence or phrase. So you had to do a lot of editing.

JR: Yeah. Mostly I went through the three pages of the application written by the student and the three pages written by their referee, and I used a highlighter to mark everything that kinda shocked me. And then I read through them again and sorted them by political theme and took the phrases that best represented each student. I took some of my personal favorites, took the ones that made me laugh, and then tried to tell a story.

PR: And now, years later, how do you feel about the ethical aspect of it? Are you comfortable with the decisions you made?

JR: Yeah, totally. If anything, I think maybe I was being too sensitive then.

PR: Did this whole experience make you feel better about dropping out of grad school?

JR: Oh, yeah, a big part of publishing this, and what kind of kicked me over the line in terms of doing it, was that I decided, "This is my master's thesis." Like, here's what I had to say about grad school.

PR: Once I started writing about the report cards, people started contacting me and saying, "Oh, if you're into old report cards, you'll probably like these old documents I have." And they'd start sending me all sorts of old stuff. Has that happened with you?

JR: Only once. A friend had moved into an old house that had been owned by a literal mad scientist — the guy's last name was Dement, I'm not kidding! He did a lot of work with X-rays for the U.S. government, but he was also an inventor. And in their basement they had, like, piles of X-rays of people's faces and skeletons and stuff, all of which was very striking. And then there were 20 or 30 journals about all his experiments, with crude drawings of all these machines he'd designed. If I'd had two months to spare, I would have made a zine about that.

PR: What would you say you've learned from this project?

JR: To just go with a feeling. I was so mad about grad school, and then suddenly this was in my lap, and it all clicked. Like, you'd think someone who'd just dropped out of school would go looking for a job, but instead of I spent the whole summer tearing through this four-foot pile of other people's lives, and it was a great experience.

Applicant always seems like a singular object. It's a bit impenetrable — I don't know how to do it again. I don't quite know why it was successful. I know I'll never find this kind of treasure trove again. You know, it's not like I did anything — I wasn't the author, I'm just the editor.

————————

Big thanks to Jesse for sharing his thoughts. If you want to purchase a copy of Applicant, it's available from Microcosm and from Amazon.